ENTREVISTA – ALAN RUDOLPH

ESPECIAL ALAN RUDOLPH

Los filmes de Alan Rudolph; por Dan Sallitt

Trouble in Mind (1985); por Dave Kehr

Trixie (2000)

Investigating Sex [Intimate Affairs] (2001)

Ray Meets Helen (2017)

El productor como apostador; por Alan Rudolph

Interview – Alan Rudolph

Entrevista – Alan Rudolph

Para esta entrevista, mandamos a Alan Rudolph una serie de largas preguntas. Teníamos una curiosidad inmensa y sentíamos que estábamos en deuda con el hombre, puesto que su trabajo significa tanto para nosotros. Cuando recibimos las respuestas, de nuevo, Mr. Rudolph lo hizo a su manera. Y fue maravilloso. Aquí queda una traducción lo más fiel posible al texto que nos envió. Las únicas modificaciones son la cursiva en el nombre de los filmes, para seguir con la tradición de nuestra revista, y en ocasiones referir el nombre del filme completo para que el lector se ubique, si Rudolph lo mencionaba abreviado. Al final os encontraréis con las preguntas originales.

RESPUESTA DE ALAN RUDOLPH

Mucho gusto.

Leí vuestro registro de mi relativamente obscura vida cinematográfica. Es curioso cómo los hechos sugieren que había un mapa implicado.

Me temo que si contestase a todas vuestras preguntas específicas tal y como están formuladas me llevaría casi tanto tiempo como vivirlas. Las respuestas son mi vida. Me limitaré a dar vueltas sobre el siguiente sumario de preguntas y luego vosotros lo disponéis a vuestra manera.

Motivaciones que te pusieron en el camino del cine. El lugar de donde proviene tu visión personal. La visión que empujó tu energía cuando empezaste, y aún estimula tu deseo de hacer filmes. Cómo has lidiado con la financiación, producción y rodaje de los filmes. Cómo has obtenido control creativo sobre ellos. De qué modo se relaciona esto con la imbricación de guiones ajenos. La conexión entre colaboradores con experiencia, o sin ella. ¿Joyce? ¿Qué has aprendido a través de las películas de Altman como espectador y para tu trabajo? ¿Cuáles son las características que te separan de Altman? ¿De qué manera, consciente o no, los años dorados de Hollywood permean tu trabajo? ¿Qué les ves de especial a los años veinte? ¿Por qué esas colaboraciones en los guiones surgieron en tus tres películas sobre los años veinte? ¿Música? ¿Cómo es trabajar con Isham? Ray Meets Helen. ¿Destilación? ¿Filme vs. digital? ¿Fue el filme una recapitulación? ¿Después de The Secret Lives of Dentists, por qué el parón? ¿Pintura? ¿Futuro?

La perspectiva fílmica es mi realidad. Soy incapaz de interpretar la vida de cualquier otra manera. Es mi lenguaje, mi proceso mental, mi empresa. No tengo elección.

Las películas han estado dentro de la burbuja de mi vida desde la infancia. En las salas, la mesa del comedor, visitando a papá en platós silenciosos y oscurecidos. Nos llevaba a ver filmes “extranjeros” y noir americano antes de que esa descripción existiese. A otros chicos no les importaba The Asphalt Jungle, los Estudios Ealing, La strada, Monsieur Hulot. Yo estaba siendo transformado para el resto de mi vida.

Encontrarse bajo el hechizo de una película es lo que me trajo aquí. Una sensación como de otro mundo. Atmósferas realzadas, lenguaje estilizado, emociones escurridizas, razonamientos extraños. Manipulación visual. Esa conexión secreta. No es real, pero se siente verdadera. Eso es lo que he estado persiguiendo. Un artificio que revele algún tipo de verdad.

Mi camino hacia la dirección de cine fue poco ortodoxo. Lo cual no quiere decir que exista un estándar. Los asistentes de dirección tienen el control de los sets de rodaje. Trabajo importante pero a nivel creativo un callejón sin salida. Aprendí el oficio de hacer películas gracias a los equipos veteranos de Hollywood. Busqué el arte del cine por mi cuenta. Exponencialmente con Altman.

La mayoría de mis filmes son fábulas absurdistas. Romances con pocas o ninguna referencia a las modas o realidades contemporáneas – excepto de forma seca. Son graciosos y serios simultáneamente, como si la broma pudiese ser válida. Apelan a sensibilidades cinematográficas, no a reglas fílmicas. En la Edad Dorada del cine americano (vuestra descripción), la gente hablaba en lenguaje estilizado, pero se comportaba de forma impredecible, con dimensión emocional. Mis filmes involucran irracionalidades sociales o personales y engaños. Abrazan el artificio, el misterio, los juegos de palabras. Se ríen de sí mismos. No siempre son lo que parecen. Una historia de amor o una farsa detectivesca pueden ser también una alegoría de la codicia política y corporativa – porque no pude obtener el proyecto sobre la codicia política y corporativa. Quizá The Moderns, ambientado con firmeza en el París de 1926, trate sobre sus propios juicios en Hollywood. Ray Meets Helen podría ser una metáfora de un cineasta persiguiendo un filme que ama solo para pagar el precio más alto al alcanzar su sueño. O no.

Esperaba comunicarme con las audiencias americanas en una frecuencia diferente a la que estaban acostumbrados. Pero sus primeras preguntas solían ser: “¿Dónde tiene lugar esto? ¿Se supone que es real? ¿Es esto serio o divertido?” Mis filmes han sido siempre como mi grupo sanguíneo – no para todos.

El control creativo es una actitud, un estado mental. Yo obtuve el “mío” al principio gracias a Altman. No es que él dijese nada acerca del corte final y todo eso. Bob simplemente suponía que al igual que él querría rodar y editar mi filme a mi manera – es decir, después de que aprendiese a usar las herramientas de montaje porque Welcome to L.A. no tuvo ningún montador a tiempo completo. Aprendí acerca de mis propios ritmos visuales, mi vocabulario. Si el control creativo significa todo eso, no voy a renunciar a él.

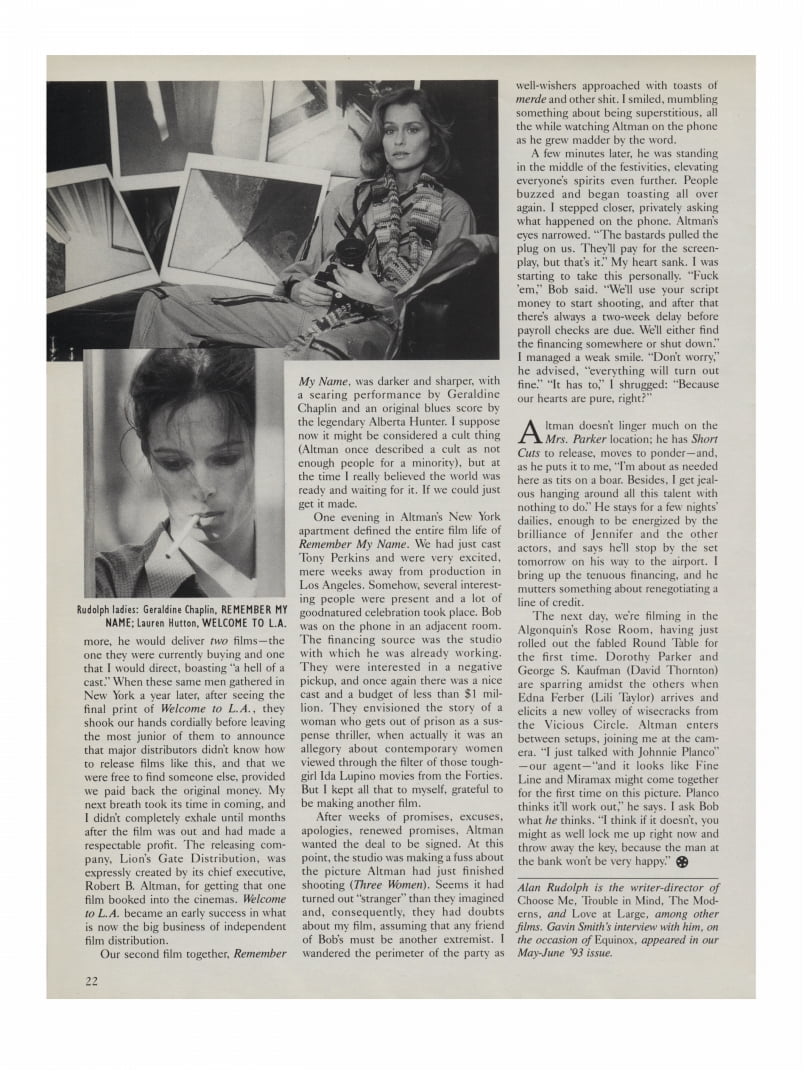

Los presupuestos económicos han jugado siempre un rol fundamental en mi metodología. Preferiría haber hecho un filme por muy poco que casi haber hecho uno por más. Altman produjo Welcome to L.A. y Remember My Name para expandir su compañía y dar a conocer una nueva voz. Los filmes tenían un reparto bien elegido, presupuestos pequeños, y estaban hechos sigilosamente, financiados por el estudio. Esos mismos estudios los rechazaron y me los devolvieron tras un primer visionado. Tuvimos que distribuir ambos nosotros como filmes americanos de art house, una categoría que no existía por entonces.

Hasta aproximadamente 1980, para mantenerme a flote mientras hacía mis propios filmes por poco o ningún dinero, tuve que aceptar algunos trabajos como director. Unos pocos se cruzaron en mi camino como desastres imposibles con prisa por empezar el rodaje. Mi especialidad. Sabía que si cumplía con lo acordado los estudios mantendrían una distancia hasta que termináramos. O les salvaba el culo o sería su perfecto blanco para culpar. Solo quería hacer un buen trabajo partiendo de malas circunstancias. Por lo general, creo que lo hice. Inmediatamente después de cada trabajo empezaba a elaborar mis propios guiones. Como dice Solo en Trouble in Mind: “Una cosa – lleva a la otra”.

Los equipos y actores me decían que trabajaba de manera diferente con respecto a la mayoría de directores. No tengo ni idea de lo que quiere decir eso. Más allá de que no tomo decisiones basándome en el comercio. Mis sets son amigables, organizados, controlados pero espontáneos. El descubrimiento, la epifanía y las buenas sorpresas son siempre bienvenidas. No hay lista de planos o storyboard. Los actores, el elemento más importante de cualquier filme, son protegidos y valorados, y reaccionan con su arte. Una escena escrita evoluciona durante cada toma, en ocasiones a lo loco. Normalmente soy el primero en sugerir variaciones. En Welcome to L.A., durante una escena complicada, seguí alentando cambios en los diálogos. Después de varios intentos frustrantes, volvimos al guion tal y como estaba escrito y revelamos la primera toma. No hay una fórmula. Las tomas largas suelen ser habituales conmigo, el diálogo enunciado con ritmos naturales, cámara, lentes, los actores todos moviéndose. El rostro humano, el mejor lugar para encontrar significado, se encuentra habitualmente al final de un plano.

Los puestos clave en muchas de mis películas están llenos de equipos ascendiendo a sus trabajos soñados por poco dinero. Acostumbro a ver algo en una persona que puede ser realzado. Los estándares creativos no cambian con la escala o el presupuesto. La habilidad o personalidad de un equipo decide la rutina diaria pero no el objetivo general. El entusiasmo no puede reemplazar a la experiencia, pero a veces es más útil. Sobre todo cuando intentas hacer lo que no se ha hecho. Algo que tiene que ver con eso de la ignorancia y la felicidad. Carreras profesionales de productores, directores de fotografía, montadores, editores, diseñadores de producción, incluso actores destacados, han empezado en mis sets. Hacer un trabajo de calidad es un motivador poderoso. Cuanto más sientas a alguien y ellos a ti, más te anticipas, canalizas, intuyes. Los recuerdos de cualquier experiencia podrán evaporarse, pero son infalibles en la pantalla. El filme es una poderosa entidad mágica y viviente. Lo que sucede enfrente del objetivo debe ser salvaguardado. Lo que hace falta para llegar ahí debe ser… ¿la vida? A menudo digo a los editores acerca del siguiente corte: “El futuro de la Tierra depende de ti”:

Trabajar con Joyce es un puro deleite. Ojalá hubiésemos hecho cada filme juntos pero ella siempre ha estado muy solicitada y comúnmente ocupada. No es solo el amor de mi vida y una fotógrafa verdaderamente talentosa, sino también una fuente calmante de energía feliz y amigable para el reparto y el equipo. Su pequeño cuerpo y formas suaves le permiten meterse en lugares compactos dando lugar a ángulos geniales y fotos vívidas, muchas recordando a productores del Hollywood clásico y vintage. Después de Short Cuts, Altman me dijo que ella era el más valioso miembro de su equipo. No solo por su gran trabajo, también por su espíritu en el set de rodaje.

Robert Altman fue el cineasta americano más influyente de su generación, dentro y fuera de la pantalla. Su actitud y arte, su innovación y rebelión, básicamente reensamblaron la producción y percepción cinematográfica americana. Y a las audiencias. Fui lo suficientemente afortunado como para formar parte de su mundo antes de que el Independiente Americano fuese una marca. Durante treinta años fuimos amigos y colegas. Tenía visión de futuro, comportándose, creando. Hollywood rehusó acoger oficialmente a Bob pero no le podía dejar ir. Era a nivel físico y mental un creador imponente que hacía su arte a su manera según sus reglas con su grupo de inadaptados. Las actitudes y audiencias americanas tuvieron que ajustarse a Altman, no al revés. Los cineastas actuales que quizá no hayan visto nunca su trabajo están influenciados por su impacto. Bob no enseñó oficialmente a nadie nada. Simplemente estaba ahí y todo el mundo aprendió mucho. Sé que yo lo hice.

No había visto ningún filme de Altman antes de pasar tiempo con él en persona, una experiencia indeleble por derecho propio. Mi reacción a su trabajo lo tendrá siempre personalmente unido. Lo que lo hace incluso más incomparable y gratificante. Estructuré expresamente Welcome to L.A. para reconocer la influencia de Bob sobre mí. Por entonces, sea cual fuere la parte de mí que iba a alterarse por Altman, ya había comenzado su proceso. Para los filmes y la vida. Éramos muy diferentes en la mayoría de aspectos, pero también nos solapábamos. De hecho, éramos tan poco parecidos como nuestros filmes. Y tan similares.

He hecho tres filmes ambientados completa o parcialmente en los años veinte. Ese periodo parecía un punto de inflexión en el comportamiento global y la innovación cultural para los próximos cien años – y subiendo. París era donde el arte de todo ello se juntó. Lo bueno, lo malo, lo encantador.

The Moderns fue mi primer intento de hacer un guion formal, escrito veinte años antes de que finalmente se llevase a cabo. Jon Bradshaw, célebre periodista, marido de Carolyn Pfeiffer, empezó a picarme el gusanillo para hacer una reescritura con él. Le gustaban mis personajes y el diálogo pero quería fortalecer la historia porque la mía tenía “toda esa chorrada de los sueños”. Trabajamos juntos durante muchos meses y luego pasamos los siguientes diez años intentando llevarlo a la práctica – en vano. Decidimos que lo menos que podíamos hacer para permanecer conectados con nuestra temática era darnos rienda suelta en los bares, cafés, restaurantes baratos de París, Nueva York, Los Ángeles, cada vez que nuestros caminos se cruzasen. Bradshaw era un editor contribuyente en Esquire y concibió un plan para acercarse a la revista con la prueba de que el guion era “El guion más rechazado de Hollywood” esperando que lo pusiesen en la portada y publicasen el texto. Ignoré la idea. Quería que nuestro filme se hiciese, no ser una respuesta del Trivial. Desgarradoramente, Bradshaw murió de forma inesperada antes de que lo consiguiésemos.

No considero Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle una película de los años veinte. Su notoriedad explotó ahí pero su vida entera fue digna de atención, aunque solo vislumbramos una pequeña porción de ella. Mi padre conoció a Robert Benchley. Cuando era un chaval, siempre estaba mirando los libros humorísticos de Benchley con dibujos de Gluyas Williams. Documentándome para el filme, su relación con Dorothy Parker desbordó mi interés por cualquier otra cosa y se convirtió en el foco de la historia a medida que avanzaba.

Investigating Sex fue una adaptación de las surrealistas Recherches sur la sexualité (1928-1932), un volumen esbelto de diálogos transcritos sin ninguna descripción más allá de los nombres de los participantes. El libro me lo dio Wallace Shawn, el cual pensó que me divertiría. Pregunté a Michael Henry Wilson, historiador fílmico francés/americano, cineasta documentalista, amigo querido, para unírseme con el fin de escribir un guion que adaptase esas discusiones. Creamos nuestros propios personajes ficticios y ambientamos los episodios en la ciudad universitaria de Nueva Inglaterra. Seguía preguntándome quién transcribió las sesiones originales. Esto se convirtió en la trama para nuestra historia. Quedé muy contento con el filme. Los financiadores no. Apenas nos desviamos del guion, que entusiastamente aprobaron. Luego se horrorizaron viendo discusiones de sexo y no representaciones del mismo, las cuales nunca estuvieron en la página. Pretendíamos acercarnos a Oscar Wilde. Ellos querían Wet ‘n Wild [salvaje y húmedo].

La música es la gran iluminadora de un filme, un puente directo a la reserva emocional de la audiencia. Si fuese un catedrático de cine (nunca sucedió), mi curso consistiría de solo una clase. Enseñaría un extracto fílmico con música. Luego lo enseñaría de nuevo sin música. Todos nos asombraríamos en cómo la intención, las interpretaciones, el ritmo, fueron alterados. Luego enseñaría el mismo extracto del filme con una música completamente diferente. Todos nos asombraríamos de nuevo en cómo todo ha cambiado. Luego me retiraría de la cátedra.

Enamorarte con una perfecta música provisional es arriesgado. Nada parece funcionar en ningún momento además. En Afterglow, durante el montaje, cometí el error de usar una pista temporal para la escena final. Sabía que era música que no nos podíamos permitir pero estaba convencido de que encontraría un reemplazo luego. Mas la versión de Tom Waits de “Somewhere” funcionaba tan transcendentalmente que teníamos que ir a por ello. Los magnates corporativos de la música no cederían el precio – maldita sea la creatividad. Lo bueno es que terminamos por debajo del presupuesto rodando, de lo contrario todavía estaríamos buscando.

Trouble in Mind es el único filme que he hecho donde la financiación, que significa certeza, estuvo garantizada desde el comienzo del proceso. Y fue dichoso. Todos los demás proyectos salieron a la niebla intentando materializarse. Siempre intenté tener preparado el siguiente filme antes de que nadie viese el anterior. O quizá no habría nunca un siguiente filme. Los productores Carolyn Pfeiffer, David Blocker y yo hicimos Choose Me juntos y el éxito de aquello creó Island Alive, una pionera compañía independiente de producción y distribución en el espíritu de Altman, Carolyn al mando. Esto fue antes de la existencia de cualquiera de las compañías que pronto le seguirían como Miramax, Fine Line, et al. Nuestro sueño fue fugaz, como es propio de ellos, pero grandiosos mientras duraron.

Mi guion para Trouble nunca aludía a la época o lugar o diseño. Era un noir directo y hard-boiled. Pero quería ensanchar eso. La música es adonde acudo para la inspiración antes de la producción o incluso de la escritura. Pero la música es invariablemente el último elemento recibido, generalmente en un punto avanzado del montaje. Para Trouble, quería cambiar el orden. Demasiada atmósfera estaba envuelta y la música alimenta la atmósfera. La trompeta debía ser la narradora, sentí. Conocí a Mark Isham, un trompetista excepcional, en su estudio del sótano. Tenía un enorme Model Synthesizer primerizo. Mark me preguntó qué tenía en mente. Se lo conté. Empezó a improvisar piezas para sintetizador y vientos hasta que reaccioné. En esas pocas horas, meses antes de filmar, Mark creó las pistas musicales que sin el mejoramiento posterior se convertirían en el 75% de la banda sonora para un filme que no se había filmado ni mucho menos montado. Desde ese día hicimos nueve filmes juntos.

Me alegro de que mencionéis Ray Meets Helen. Fue única en ciertos aspectos – excepto por la indiferencia de los críticos y la audiencia. El guion fue escrito años antes y pasó por varias ideas de reparto pero nunca encontró tracción. No estaba considerándolo activamente como un filme que hacer. Sabía que las audiencias contemporáneas y los financieros no querían tener nada que ver con un romance simple y anticuado. Lo que, por supuesto, se convirtió en la razón exacta para ir a por ello. Cuando solo una porción del dinero fue reunida habría sido fácil o quizá sabio seguir adelante. En vez de eso, reducimos el tamaño. El presupuesto de rodaje, ese asunto de nuevo, fue el más bajo de cualquier película legítima que haya dirigido e igual al de Return Engagement, el documental en 16 mm que hice en 1982. El equipo era en su mayoría aleatorio y estaba allí gente joven entusiasta que quería ser parte del negocio del cine. El montador nunca había editado una película. El director de fotografía era un joven operador. El diseñador de producción era nuevo en el oficio o cualquier otro trabajo dentro del mundo del cine y tenía veintidós años. Sería filmada bajo un contrato industrial llamado “ultrabajo presupuesto”. Lo que significa gratis. No nos podíamos permitir un guardia así que la cámara nunca estuvo autorizada en ninguna calle. Los sets principales, el restaurante donde se conocen y la casa a la que Helen se muda, eran la sala de estar del productor y el piso superior. Sabía cuáles eran nuestras limitaciones y esculpí en torno a ellas. Le dije a todo el mundo que no estábamos haciendo un filme sino un regalo para más tarde cuando no estuviese compitiendo con nada contemporáneo. Fue simplemente un puro acontecimiento cinematográfico. El principal atractivo, como siempre, eran los actores. Trabajar con Keith Carradine era razón suficiente para mí. Sería nuestro sexto filme juntos y el primero en veinticinco años. Sondra Locke era una amiga de Joyce desde hace mucho tiempo. Una actriz con talento que no había trabajado durante décadas porque la industria la puso en la lista negra a causa del decreto rencoroso de su examante/actor superestrella, entró en la conciencia de nuestro reparto en el último minuto. Esa idea me creó presión. Afortunadamente, estoy profundamente alegre con los resultados. Fue un rodaje totalmente disfrutable, uno de los mejores. Sondra estuvo más feliz que en ningún otro filme y su interpretación es divertida, evocadora e inolvidable. El filme adquirió un significado especial unos meses después de su estreno cuando Sondra falleció a causa de un cáncer, una condición que sabía que existía durante el rodaje pero que se guardó para ella misma. Será siempre para mí el filme más valioso que haya hecho.

Hicimos Ray Meets Helen en digital porque, bueno, no había más opciones. No afectó al rodaje demasiado desde mi perspectiva. Excepto por los dailies (tomas diarias). Los dailies siempre eran el momento más destacable de los rodajes para mí, la recompensa por el trabajo duro. Altman me enseñó eso. Invitaba a todos a los dailies, especialmente a los actores. Quería crear una experiencia igualitaria con gente apoyándose entre sí y no encerrada en perspectivas ególatras. Era estimulante, pionero, y divertido. En mis filmes mezclaba la música con cada toma a través de altavoces, experimentando y aprendiendo. A todo el mundo le encantaba. Para mí la lente es el narrador de un filme. Nunca miro a los monitores durante tomas en ningún filme, siempre me coloco cerca de la cámara observando a los actores, el dolly, y el zoom. En los días de 35 mm, nadie sabía lo que buscábamos aparte del equipo de cámara y yo. Pero cada noche todo aquel que quisiese ver podía venir a la fiesta y sorprenderse. Con el digital, todo el mundo tiene un monitor mientras una toma está siendo rodada, por lo tanto no hay necesidad de dailies. No me gusta eso.

Como habéis señalado, más o menos trabajé todo el tiempo hasta después de The Secret Lives of Dentists en 2002. Luego me tomé a la vez todos los intervalos normales entre filmes y no trabajé por quince años. Me enseñé a pintar, escribí parte de mi mejor material, pero no intenté lanzar nada. Todo en la industria del cine fuera de mi perspectiva creativa era siempre diferente y algo hostil. Pero jamás me molestó. Lo que quiera que estuviera haciendo el resto nunca afectó demasiado lo que hice. No se puede negar que mi contador estaba atascado en “poco comercial” y el camino por delante siempre fue escarpado. Mis trabajos más logrados e inventivos como Trixie o Breakfast of Champions siempre fueron los más rechazados. Todo hizo daño en alguna parte, estoy seguro, pero no en lo más profundo, donde importa de verdad. Como dijo el brillante novelista Tom Robbins, it’s not a career but a careen.

A causa de que todos excepto uno de mis filmes fueron hechos antes de la era digital/Internet, apenas estrenados por compañías extintas, y actualmente sin estar en streaming en un reloj de pulsera o en un cabezal de la ducha cerca tuyo, me he preguntado qué les podrían parecer a espectadores desprevenidos que se topasen con ellos. La gente quizá no reaccionaría, pero siento que los filmes son un tanto atemporales. Nunca se parecieron a ninguna cosa, incluso cuando se hicieron.

Era obvio desde el comienzo que mi sueño sería imposible si hubiera hecho caso a las señales de alarma. Además, nada es imposible si desechas lo evidente. Qué emocionante.

Buena suerte,

Alan Rudolph

***

Días más tarde, Mr. Rudolph nos refería que había conocido a Antonio Banderas hacía años en un festival de cine. El actor español le contó al cineasta que Pedro Almódovar ponía a su troupe todo el rato Choose Me (1984), porque eso era lo que buscaba. El cineasta desea que fuese cierto, ya que considera a Almodóvar uno de los grandes artistas de la historia del cine.

NUESTRAS PREGUNTAS ORIGINALES

1.- Para empezar, nos gustaría que nos hablaras de cuáles fueron tus motivaciones para lanzarte a hacer cine, de dónde viene tu visión tan personal. Sabemos que tu padre, Oscar Rudolph, tuvo una larga carrera dentro de las industrias del cine y televisión, estando conectado a ellas durante toda su vida, realizando todo tipo de trabajos: desde un rol de actor en una película muda con Mary Pickford hasta extra durante la Gran Depresión, luego asistente de Cecil B. DeMille o Robert Aldrich, trabajos como director de TV… Refieres que cuando eras niño te llevó a los estudios de la Paramount y que no tardaste ni un segundo en sentirte, entre esos gigantescos decorados, como en casa. El artificio pasó de repente a significar para ti la única realidad, el cartón piedra se incrustó pronto en tu biografía. Sabemos que a mediados de los sesenta filmaste decenas y decenas de filmes cortos en Super-8, y aunque no tenemos claro si en los siguientes trabajos fuiste primer asistente de dirección, segundo asistente o trainee, tu nombre aparece acreditado en Riot (1969), The Big Bounce (1969), The Great Bank Robbery (1969), The Arrangement (1969), Marooned (1969) y The Traveling Executioner (1970), antes de lanzarte a filmar junto a unos amigos Premonition (1972), donde sí ejercías de director.

También tenemos constancia de que después de rechazar en un primer momento ejercer de asistente de Robert Altman, tras ver McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) te convenciste y empezaste a asistirle en filmes como The Long Goodbye (1973), California Split (1974), Nashville (1975)… y ejerciendo de coguionista en Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976).

Tras Nightmare Circus (1974), un proyecto que te fue traspasado, escribes y diriges Welcome to L.A. (1976), el primer filme donde presenciamos algunas de las constantes que te acompañarán durante toda tu carrera. En un artículo pionero sobre tu cine de Dan Sallitt de 1985, él te imaginaba ligeramente como Carroll Barber, el personaje de Keith Carradine en Welcome to L.A. En aquella película, todos los personajes principales lanzaban unas miradas inconsecuentes a cámara, sin atreverse a sostenerlas demasiado tiempo, mostrándose algo inconscientes en medio de su confusión sentimental. Carradine, quien había practicado una sana promiscuidad durante todo el filme, acaba condescendiendo con ternura a Karen Hood (Geraldine Chaplin) y Linda Murray (Sissy Spacek), sosteniendo una mirada a cámara, terminados los créditos, que certifica que el personaje ha adquirido, en el proceso, algo de sabiduría y comprensión, que ha conseguido alejarse un poco del enjambre. La venganza dulce de Emily en Remember My Name (1978), cómo consigue librarse del anillo aunque siga un poco mentalmente entre las rejas ─al igual que su exmarido al que ha atrapado de nuevo, Neil Curry (Anthony Perkins)─, nos retrotrae a sensaciones similares, además de que en este cuarto largometraje tuyo, tercero en el que ejerces a la par labores de guion y dirección, se introducen ya el bar y el neón como paradigma del microcosmos del cóctel de sentimientos.

¿Qué nos puedes decir de la visión que te impulsó cuando empezaste, y que te sigue impulsando ahora a hacer cine?

2.- Agradeceríamos que nos intentaras transmitir, siendo conscientes de que levantar cada una de tus películas ha supuesto un mundo y de que tu carrera ha transitado por diferentes etapas, cómo abordas la financiación, producción y el rodaje de tus filmes. Nos parece muy sorprendente que durante treinta años ─desde Premonition hasta The Secret Lives of Dentists (2002)─ hayas podido realizar veintiún filmes sin apenas descanso entre ellos, desde 1984, e incluso haciendo de guiones ajenos filmes valientes, sorteando los innumerables cambios que ha sufrido la industria cinematográfica. Grosso modo, las cuentas arrojan un filme por cada año y medio de trabajo. En este sentido, te hemos escuchado en otro lugar afirmar que probablemente la decisión más importante que uno puede tomar en su vida es «cómo de importante es para ti el dinero, qué harías por dinero». También que tu mayor dificultad en los diferentes eslabones de la cadena que supone llevar a término una película ha atañido a la financiación.

Todas las anécdotas y pormenores que nos puedas referir en este sentido nos serán interesantísimas, ya que estamos ávidos de curiosidad por saber en detalle cómo te las has arreglado para tener tal control en la producción, filmación y corte final en tus películas. Y cómo todo esto se relaciona con ir intercalando películas de guiones ajenos (suponemos que acabarás moldeándolos igualmente) con proyectos donde la página blanca empieza directamente enfrente tuyo.

3.- En Choose Me, elegiste a gente del equipo que nunca había trabajado en producciones al uso ─camarógrafo, editor─, práctica que has seguido llevando a cabo hasta Ray Meets Helen (2017), donde dices haber incluido en el equipo a gente realmente joven.

A la vez, mezclas a esta gente sin experiencia con fieles tuyos muy constantes. En la fotografía pensamos en Jan Kiesser, en Elliot Davis, en Toyomichi Kurita, en Florian Ballhaus, en David Myers… todos ellos colaboradores tuyos en más de un filme. También en Pam Dixon Mickelson, directora de casting, colaboradora desde Made in Heaven (1987) en todos tus filmes, excepto Mortal Thoughts (1991). Musicando, sobresale Mark Isham. James McLindon ejerciendo diversos trabajos como productor ejecutivo. Y, como no, pensamos en Joyce Rudolph, tu mujer, estando su trabajo de fotografía presente en Choose Me, Made in Heaven, The Moderns (1988), Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994), Afterglow (1997), Trixie (2000), Investigating Sex (2001), The Secret Lives of Dentists, Ray Meets Helen…

¿Puedes hablarnos de cómo es la relación de estos profesionales con más experiencia de trabajo en equipo codo con codo con talentos noveles con muchas ganas de trabajar? Sabemos que te resulta excitante trabajar con estos noveles aún no habiendo adquirido ellos “malos hábitos”. ¿De qué modo crees que la estética de tus filmes en parte es deudora de esta mezcla de experiencias?

4.- Sabemos de tu lazo de filiación y deuda por mecenazgo amistoso con Robert Altman. Pero aparte de su ayuda para levantar la financiación de algunos filmes tuyos y de tu aprendizaje siendo “assistant director” o coguionista a su mando, nos interesa particularmente qué es lo que realmente has aprendido mediante sus filmes como espectador, o como trabajador (por ejemplo, su uso del zoom in lento y de las dolly). Has mencionado que McCabe and Mrs. Miller supone un punto de inflexión para la música en el cine; también nos ha hecho reflexionar lo que una vez afirmabas sobre que Altman solía desetabilizar la escena, a sus actores principales, cuando algo no funcionaba, lanzando a un extra o a un personaje que no estuviera en el guion o la toma. Jurabas que en la mitad de sus películas la estrella vagamente estaba en el encuadre, sino en su borde mismo, y la película iba sobre todas las demás cosas. ¿De qué manera te ha influido esto a la hora de abordar tus rodajes, al igual que la herencia altmaniana de visionar los dailies con los actores y el equipo? Ese es un punto que conecta también con el hecho de que dejes a los actores cambiar el guion si es necesario, ¿esto ocurre en los ensayos o durante la propia toma? ¿Y cómo conjugas esta tendencia de dar manga ancha con los días limitados de rodaje y presupuestos ajustados?

Por otro lado, aunque entre tu visión y la de Altman existía sin dudarlo una sensibilidad común, percibimos una gran diferencia, como escribe Sallitt, en vuestro cine de los setenta: mientras que en Altman se daban momentos donde el punto de vista se externalizaba, sugiriendo una perspectiva pavorosa y cósmica (Dave Kehr) sobre las personas, tu cine siempre ha propuesto una fascinación empática, casi paterna, respecto a los personajes, la cual hace brotar de ellos el enigma. ¿Qué características crees que han sido, desde el principio, las que han distinguido tu visión del mundo de la de Altman?

5.- Dicho esto, tu filmografía tomada en completo, incluso viendo solo uno o dos filmes, evidencia una personalidad propia arrablante de cualquier influencia unívoca. Nosotros vemos en tus filmes muchas herencias bien asumidas del cine americano clásico, anterior a los años 60, para acotar la cronología, y en alguna ocasión lo has ratificado (melodramas de los 40, etc.). En una escena de Mortal Thoughts (1991), John Pankow referencia el look de Glenne Headly como reminiscente de Greta Garbo, actriz esta que canaliza Geraldine Chaplin en Welcome to L.A. mediante una alusión explícita constante a Camille de George Cukor (1936). Al principio de Made in Heaven, los personajes salen del cine de ver Notorious de Alfred Hitchcock (1946). Luego, Nathan Lane, en Trixie, referencia a Maurice Chevalier y Mimi, tema hecho famoso en Love Me Tonight (1932) de Rouben Mamoulian (en tu audiocomentario para el DVD referenciabas que una parte de su número, el de Kirk Stans, fue improvisado por el actor). Citamos solo algunas de las referencias evidentes, pero también conocemos ese proyecto que tenías en mente de adaptar al cine la autobiografía de Man Ray. En definitiva, ¿de qué manera, consciente o inconsciente, permean estos años dorados de Hollywood, previos a la considerada modernidad cinematográfica ─a veces asociada contigo, para nosotros y creemos para ti, coyuntural y erradamente─, tu labor como artista?

6.- Has realizado tres películas cuya historia toma lugar en los años veinte, una ambientada en Nueva York ─Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle ─ y dos venidas de París ─The Moderns e Investigating Sex─, aunque acabaste situando las reuniones de los surrealistas, plasmadas por José Pierre en las Recherches sur la sexualité, en un Cambridge, Massachusetts, ficticio, recién desencadenada la Gran Depresión y con una Ley seca tardía. Indudablemente, los tres filmes tienen en común el centrarse en unos personajes inmersos en unos grupúsculos cuyo vicioso funcionamiento consigue escindirlos, en grados variables, de la sociedad y sus convenciones, confiriendoles una distancia innovadora ─germen del genio─ la mayoría de veces traumática, incluso peligrosa, o directamente abocada a la perdición para los individuos que los componen. ¿Qué tienen los Roaring Twenties en EEUU, y los Années folles en Francia, que tanto te seducen? ¿Quizá las vanguardias, las tertulias donde no deja de removerse la conversación? ¿Quizá cierta locura feliz, efervescente, fugaz, ligada al expansionismo y al desarrollo económico destinados al hundimiento del 29, una época que quedaría grabada luego en las conciencias como un hito melancólico y romántico? Tienes comentado que mucha gente piensa en los años 20 como el apogeo del arte moderno, pero que eso ocurrió cuando los turistas empezaron a llegar a París y expandir la palabra. The Moderns, para ti, tenía mucho que ver con la sociedad de la falsificación y los mitos de la Ciudad de la Luz en esa década citada.

También nos llama la atención que para estos tres filmes históricos te ayudaras de coguionistas ─de Jon Bradshaw para The Moderns, de Randy Sue Coburn para Mrs. Parker, que había novelizado tu filme Trouble in Mind (1985), y del francés Michael Henry Wilson (también colaborador durante cuarenta años de la revista Positif) para Investigating Sex─, ¿cómo se dieron estas colaboraciones? ¿Tiene algo que ver la envergadura respectiva de los proyectos y la necesidad de asesoramiento histórico?

7.- En una entrevista que concediste con motivo de la retrospectiva que te hicieron en 2018, en el New York’s Quad Cinema, dijiste que probablemente el público que apreció algunas de tus anteriores películas, y al que le parecía bien que se recuperase el cine del Alan Rudolph de los ochenta, posiblemente no llegaría a comulgar con Ray Meets Helen. Nosotros, sin embargo, coincidimos contigo en que es tu filme más destilado (distilled) y donde las características de tu cine se condensan hasta lo esencial (everything’s right down to the bare bones), sintetizando gloriosamente tus inclinaciones, amores y trayectoria.

Aunque te hemos escuchado afirmar que, según tu experiencia, esta incursión en el formato digital no ha distado mucho a la hora de rodar de cuando has filmado en celuloide durante toda tu carrera, apreciamos en Ray Meets Helen una soltura y unas innovaciones, incluso una desvergonzada confianza en lo filmado, solo comparables a cómo entregabas enajenadamente el alma de Breakfast of Champions (1999) a unos locos insertos de efectos especiales en calidad vídeo. El modo en que se introducen los cromas y trucajes caseros en Ray Meets Helen llega a arrebatarnos el corazón: cuando ambos viajan por el mundo sin levantarse de la mesa del restaurante, embriagados por el champán, encapsulados en imágenes de archivo que parecen un souvenir; o cuando Ray lanza patéticamente pero seguro de sí una mirada de desprecio a Ginger Faxon, recortada en la parte superior de la esquina izquierda de la pantalla; las apariciones de Mary a Helen, también las de los sueños truncados del Ray joven, ecos diagonales de Nick Hart, también boxeador, en The Moderns; finalmente, el baile de los actores en los créditos que remata la fantasía y rivaliza en subversión golosa a los de David Lynch en Inland Empire (2006). También decías que una de las pocas diferencias entre el celuloide y el digital es que no existe el evento del laboratorio de revelado llamándote para recoger los dailies, o que meramente las tomas podían ser más largas; nosotros vemos las virtudes de este segundo caso, por ejemplo, en la cena donde Ray conquista a Helen, en cómo se cortan los planos en suave movimiento, propios de algún tipo de automatismo del cine digital…

En retrospectiva, ¿qué te ha aportado rodar esta película en digital con respecto a tus experiencias anteriores en celuloide y qué ha supuesto para ti a modo de recapitulación, esperamos que con continuidad, de tantos años de trabajo dentro del cine?

8.- Después de terminar Equinox (1993), te referías a un estado mental donde creías haber llegado a una línea divisoria en tu trayectoria, y que ese filme era lo más lejos que habías podido llegar en ese grupo conformado por lo que tú llamabas “hip-pocket movies” o “urban fables”, requeridoras de la participación de la audiencia, ella misma convirtiéndolas en dichas fábulas. Vista tu obra en retrospectiva, claramente se nos antoja acaparadora de diversas estéticas unidas al drama, la narración y tu proyecto formal. Tenemos esos filmes de los años 20, tus incursiones en guiones ajenos llevándotelos a tu mundo, y luego esas “hip-pocket movies”, como Welcome to L.A., Choose Me, Trouble in Mind, Love at Large (1990) o Equinox. En estos filmes, al leer uno críticas de la época, se suele encontrar repetidas veces con la palabra pulp, aludiendo a una estética quizá deudora, apasionada, pero tratada sin ninguna condescendencia, que podemos encontrar en muchas películas B de los años dorados de Hollywood o en ciertas revistas y novelas. Nos preguntamos si has tenido alguna fuente de inspiración particular a la hora de abordar historias tan concretas como Equinox, donde por tratamiento, psicología de personajes y situaciones, uno no puede evitar pensar en una suerte de continuismo sólido con una tradición previa… ¿Dónde te sientes ligado, sentimental y emocionalmente, cuando escribes y filmas esas fábulas? Sabemos que Kurt Vonnegut, la ironía, el humor, han sido un punto de unión en la amistad que te une con Keith Carradine. ¿Podrías ahondar un poco más en estas filiaciones?

9.- No podemos olvidarnos del papel de la música en tus películas. Tenemos entendido que para pagar los derechos de los temas de Teddy Pendergrass que permean Choose Me tuviste que aceptar otro encargo, Songwriter (1984). El uso muy deliberado de la música de Richard Baskin en Welcome to L.A., Alberta Hunter en Remember My Name, Leonard Cohen en Love at Large, Tom Waits en Afterglow (de este veíamos un afiche en una escena de Made in Heaven y hemos pensado en su etapa setentera de crooner al ver merodear a Carroll Barber por las calles angelinas en una noche que parece no acabar)… Los ejemplos son numerosos y se pliegan con la atmósfera de tus filmes sin asfixiarla, un acompañante dócil. Y como pareja, parece que en Mark Isham encontraste una mina de oro, pues sus bandas sonoras han ido de la mano con muchos filmes tuyos. Cuéntanos un poco cómo se establece esta relación entre vosotros dos, de qué manera informa la música de Isham a tus filmes y en qué momento empieza él a componer, el tipo de indicaciones que le das, etc. Y cómo todo esto lo intercalas con dichas canciones, porque suponemos que crees necesario salirnos por un momento de la BSO original para tomar un préstamo que realmente aportará un matiz único a la escena.

10.- Tras The Secret Lives of Dentists ─un filme que, partiendo de un guion ajeno, demuestra una mutabilidad humilde apoyada en la escritura de otro, concuerda con tu visión del mundo y es coherente con las conclusiones que has ido desarrollando durante toda tu carrera (los vericuetos de la conyugalidad, las proyecciones excitantes que espolean fantasías fragmentarias, el consentimiento cruel y la conciencia que David Hurst adquiere al final sobre su matrimonio, etc.)─, un proyecto con una puesta en forma muy generosa para con el espectador, una de tus películas más universales que por mala fortuna pasó casi directamente al direct-to-video, y tuviste un parón de casi quince años hasta Ray Meets Helen. ¿Qué motivos hay detrás de que tu carrera como cineasta se detuviera? Suponemos que gran parte de la culpa la tendrán las dificultades para encontrar financiación. Y, ¿qué puedes decirnos sobre tu afición a la pintura, otra inclinación tuya con la que, tenemos entendido, ocupaste el tiempo?

¡Y eso es todo! Muchas gracias por tu tiempo, Alan. Esperamos con grandes expectativas otro filme tuyo. Tus películas formarán siempre parte de nuestras vidas.

Nuestros mejores deseos.