ENTREVISTA – NOAH BUSCHEL

ESPECIAL NOAH BUSCHEL

Glass Chin (2014)

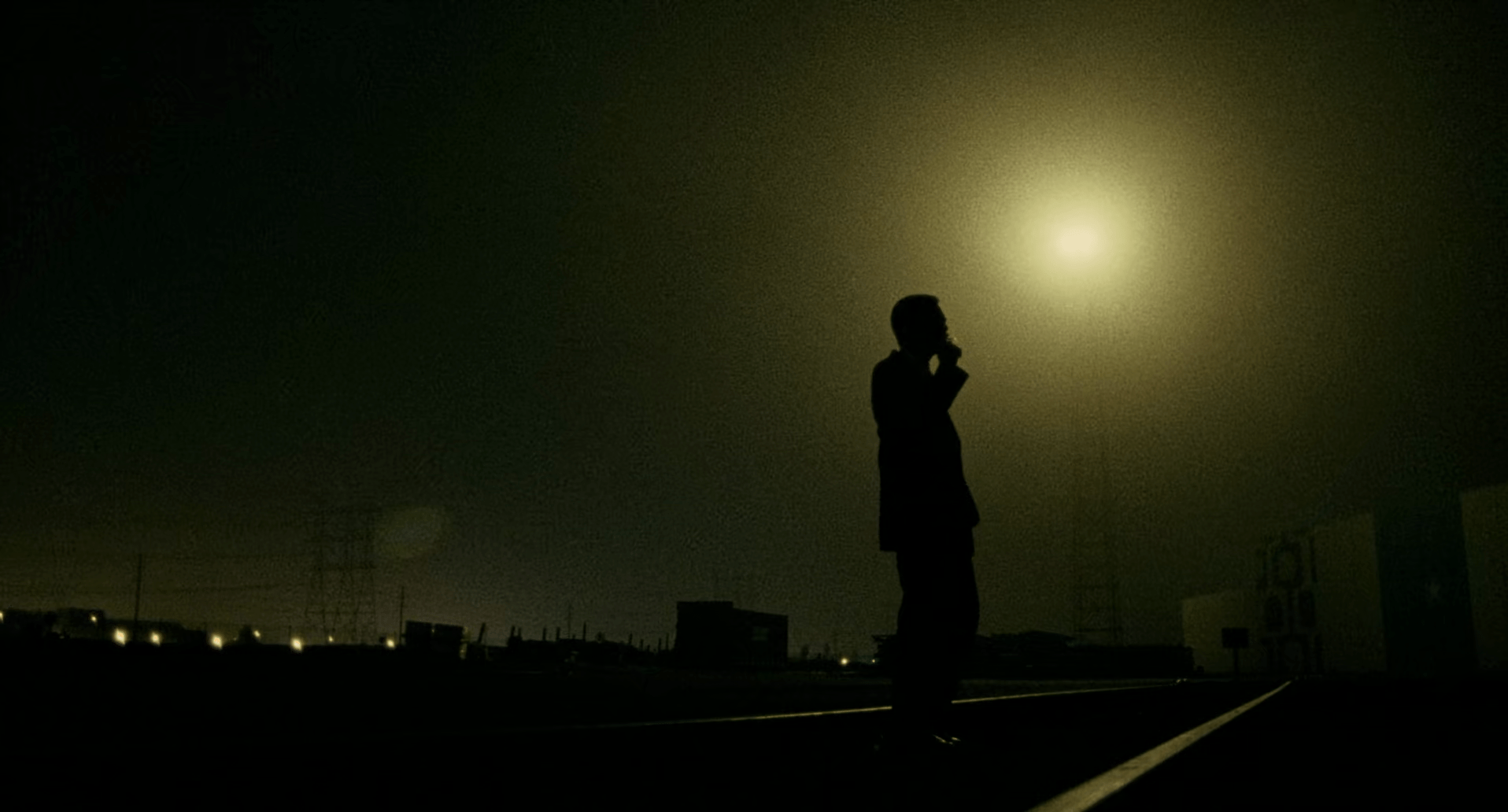

The Man in the Woods (2020)

En el sendero, fuera de la ruta; por Gary Snyder

Interview – Noah Buschel

Entrevista – Noah Buschel

El pasado enero descubrimos los filmes de Noah Buschel. Unido al sentimiento de euforia que transmite al espectador abordar una obra que le entusiasma, se unía por aquel entonces el desconcierto ante la casi total falta de discurso crítico alrededor de los filmes del cineasta en cuestión. Más allá de aportar unos cuantos textos reflexionando sobre su obra, sentimos que debíamos contactar con Noah y darle la oportunidad de explayarse. Cuando establecimos contacto, descubrimos a una persona atenta, generosa, con disposición a resolver cualquier tipo de duda e incluso a ofrecernos atención de más. Esperamos que nuestras preguntas sirvan como pequeña recolección de la trayectoria del cineasta. Por encima de todo, nuestro entusiasmo lo depositamos en el hecho de poder compartir la respuesta de Noah, una réplica unitaria a nuestras largas cuestiones que arroja luz sobre su propia obra y el presente que vivimos, dándole un espejo en el que mirarse. Al final os encontraréis con las preguntas originales.

RESPUESTA DE NOAH BUSCHEL

Al principio lo hice porque parecía precioso, rodar en lugares desiertos. Estábamos haciendo esta película sobre un internado y el centro estaba cerrado durante el verano. Día tras día me encontré a mí mismo tímidamente apartando a los extras. Tenía que susurrarle al asistente de dirección– “perdona, ¿puedes hacer que esos chicos se vayan a casa?” Era más interesante ver a los actores caminando a través de salas vacías y gimnasios y vestuarios. En el guion, los estudiantes eran como fantasmas merodeando a través del bardo. Filmar la escuela como una ciudad fantasma tenía sentido. Así es como probablemente describiría al instituto en general– fantasmas merodeando a través del bardo, entre cuerpos, entre vidas.

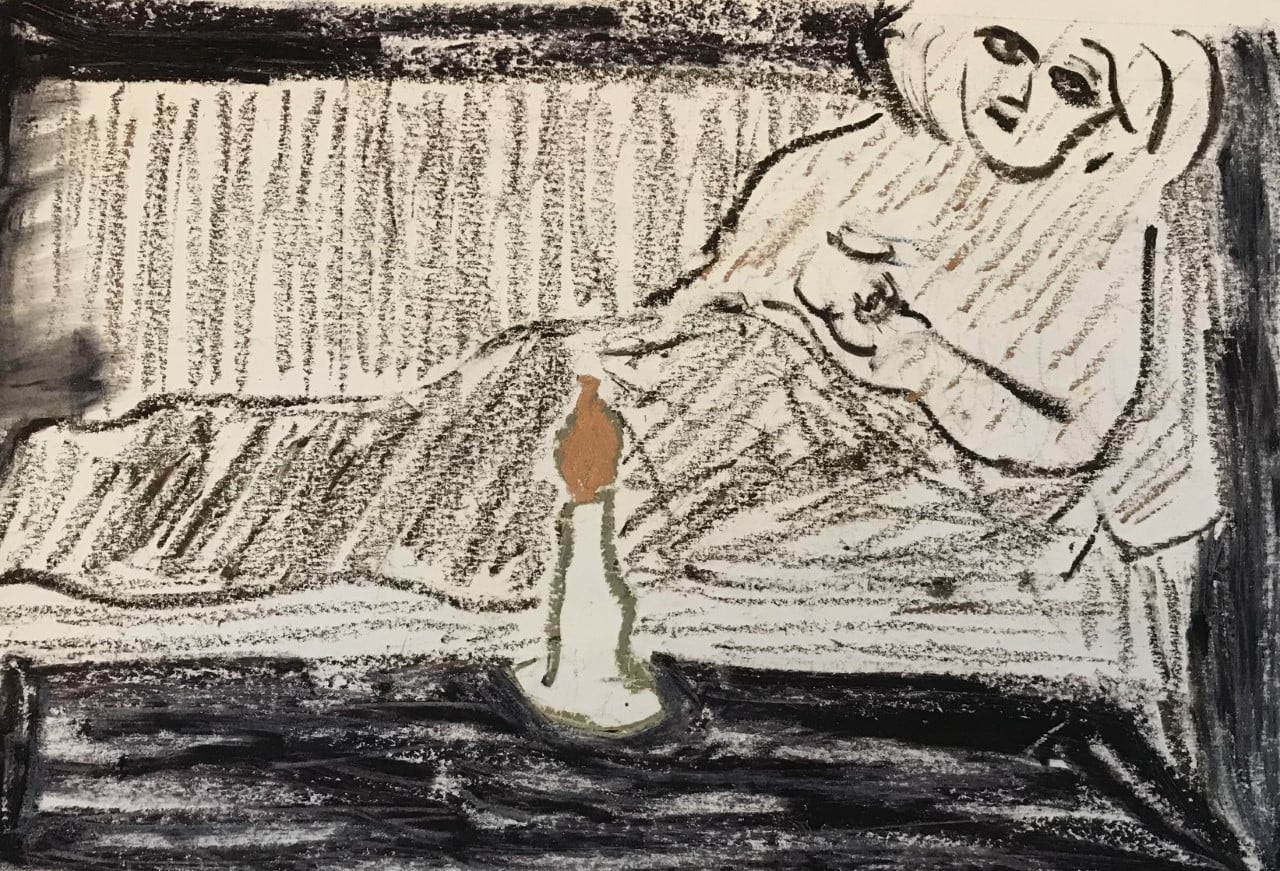

No hay mucho drama en mis películas. Pero si hay drama, pienso que viene de la soledad. Y por ello me refiero– la soledad es romántica, y es bonita, y es cool, y es quizá incluso apacible y confortable. Pero es también amenazadora. Las luces de Navidad en el exterior de una casa vacía. Un tren con casi nadie dentro. Una calle desolada. Los personajes en mis películas están casi siempre al borde de ser tragados por esta soledad. El aparentemente inocente estilo americano de los 50 que establezco en todas estas películas— neones zumbando, nieve cayendo en un diner, un camión de Coca-Cola reluciente y rojo– esa es la cualidad seductora de la soledad. Parece tan romántica al principio. Cuando tienes diecisiete años y fumando un cigarrillo y caminando por Broadway a las 3 AM. Incluso la locura y el insomnio parecen glamurosos al principio. Pero pienso que mis películas son realmente antiromance. Todas tienen estos clásicos tropos americanos, pero al final, el amor que nos salva es más mundano y práctico que eso. Como en Sparrows Dance. El amor que realmente la ayuda a salir de sí misma no es sentimentaloide en absoluto. Es el tipo de amor que detiene el suicidio. Es un amor ordinario que tiene sus pies firmemente plantados en el suelo. Es un amor que despierta a uno. Así, mis películas están destinadas a sentirse como sueños atemporales, como flotar en un baño caliente. Pero al final, dicen– ey, despierta. No te ahogues en el Sueño Americano. No caigas en la trampa. No seas cool. Abre tu corazón. Es un asunto de vida y muerte. Realmente estoy tratando de despertarme a mí mismo.

Ver nuestra propia sombra es el trabajo, supongo. Hacer la oscuridad consciente. Es el trabajo de un cineasta, de un actor, de un meditador, de un ser humano. Si llegamos a vislumbrar hasta nuestra propia sombra, se hace más difícil ir por ahí echando la culpa al gobierno, o culpando a Putin, o culpando a un examante, o culpando a un antiguo amigo que sentimos nos ha traicionado, o culpando a la NRA, o culpando a Hollywood, o culpando a la Cultura de la Cancelación, o culpando a Internet… Es empoderador dejar de acusar con el dedo. Todo lo que encontramos es nuestra propia mente, así que acusar con el dedo es algo absurdo. Pero porque somos tan valiosos para nosotros mismos, nos gusta pretender que las cosas turbias no tienen nada que ver con nosotros. Y luego podemos volver a nuestra rutinas santurronas. Es como andar por ahí con una actitud—“esta persona borracha y sin techo no soy yo, esa debutante de plástico no soy yo, esa pila humeante de mierda de perro no soy yo, ese exabrupto violento de la esquina no soy yo… oh, hay una rosa esplendorosa en la ventana de la floristería— ¡eso sí soy yo! Voy a tomar una foto de la rosa y postearla en Instagram. Y verdaderamente basar mi identidad alrededor suya”. O “oh, hay una foto de Martin Luther King en la ventana de la librería— ese soy yo. Y hay una foto de Trump en la portada del periódico— ese no soy yo”. Cuando negamos nuestra propia sombra, eso nos hace muy frágiles. Como una muñeca china de porcelana, nos volvemos fácilmente rompibles. Nadie pretende rompernos, es solo lo que ocurre cuando nos apreciamos tanto a nosotros mismos.

Por largo tiempo intenté separar lo bueno y lo malo, situando al santo en una esquina y al demonio en la otra. Fui por la vida intentando escoger y elegir con quien estaba conectado y con quien no lo estaba. Pero haciendo eso, solo terminé encadenándome a aquello que negaba. Dejar ir no es una negación, es una afirmación, un viraje hacia. Cuantos más enemigos bloqueemos, y cuantos más cabezas de turco sean objeto de nuestros tweets —menos sabremos quiénes somos. Me parece a mí. Terminamos viviendo nuestras vidas basándonos en el autoengaño de una proyección. Podrías llamar a esa proyección una película, imagino. En esa película, todas las partes desheredadas de nuestro ser emergen como el otro. Y llevamos por ahí esta narrativa de que estamos separados. Lo que conduce a dos maneras de reaccionar a todo. Eso está bien, lo quiero. Eso no está bien, no lo quiero. Todas las personas y todas las cosas son objetificadas, en cierta medida, si no nos damos cuenta que somos nosotros.

En el momento en el que una industria entera se concibe alrededor de la impermanencia del registro, va a haber mucha gente asustada que vaya en tropel. Gente que no quiere ver que básicamente esto es completamente impermanente y vacío. Puedes oír la desesperación en las voces de algunos preservacionistas fílmicos. Pero las películas no son para siempre. Incluso en Internet, que tampoco es para siempre. Eventualmente se desvanecerá. Quizá Scorsese será mostrado en Marte dentro de mil años a una multitud de mitad humanos/mitad robots, pero eso solo significa que su película tuvo un recorrido ligeramente más largo. Eventualmente su recorrido también habrá terminado.

Parcialmente entré en el cine por mi propio miedo a la impermanencia. No es blanco o negro– También fui inspirado por muchos cineastas y actores cuando era joven y tenía un amor genuino por las películas. Y por hacerlas. No hay nada como estar en un rodaje nocturno cuando eres libre y juegas y te olvidas de ti mismo. Luego, la grabación es simplemente una consecuencia. Pero pienso, en términos de mí mismo entrando en el mundo del cine y a menudo quejándome de él, pienso que hubo mucha proyección sucediendo allí. No quería ver mi propio miedo de… sí, mi propio miedo del gran vacío.

¿Conocéis este poema de Antonio Machado?

Nunca perseguí la gloria

ni dejar en la memoria

de los hombres mi canción;

yo amo los mundos sutiles,

ingrávidos y gentiles

como pompas de jabón.

Me gusta verlos pintarse

de sol y grana, volar

bajo el cielo azul, temblar

súbitamente y quebrarse.

El proyecto de Denis Johnson, Doppelgänger, Poltergeist, no lo voy a dirigir. No lo podría hacer como director incluso si quisiera. Solo puedes hacer un determinado número de filmes extraños y pretenciosos hasta que las agencias se dan cuenta, pero también, la última película que hice, The Man in the Woods— supe mientras la hacía que iba a ser mi última película como director. Mi primera película era un filme de internado, y también lo fue esta última. Nunca fui a un internado, pero es genial para escribir acerca de adolescentes, porque no tienes que tener escenas con padres. Como A Separate Piece y Catcher in the Rye— sin padres, simplificado. Pero de todas formas, concerniendo a Doppelgänger, Poltergeist, trata acerca de la reencarnación. Como también de muchas otras cosas: gemelos, Nueva York, 11 de Septiembre, enamorarte de fantasmas, cómo lidiamos con el suicidio de un ser querido, ser un artista outsider versus un artista mainstream… Simplemente es una historia increíble que me resultó muy familiar. Y la parte de la reencarnación era uno de los componentes que realmente hizo clic. Este es el día y la época de la identidad. Donde la gente se agarra a sus identidades y cosas como el género son extremadamente definitorias. Series de televisión y películas y carreras enteras están construidas alrededor del género. Pero en la historia de Denis Johnson, la identidad está más en flujo. Y leyéndola casi se sintió como medicina. Me recordó que agarrarse a la identidad es la raíz del sufrimiento. Cuando verdaderamente veo a alguien, parece estar transformándose entre la juventud y la vejez. Y son una mujer en un segundo y un hombre al siguiente. Ese, para mí, es uno de los signos de una gran interpretación. Cuando un actor se está transformando. Hay muchas interpretaciones de Gena Rowlands donde parece una mujer de mediana edad y luego un segundo después es una niña de cinco años. Y ni siquiera se ha movido. Solo está sentada en una cabina, Jill Clayburgh es así también algunas veces. Amy Wright, que ahora creo que enseña en HB Studio. Eijirō Tōno. Setsuko Hara. Richard Farnsworth. Garbo. Por supuesto, Brando. La escena del bar con Eva Marie Saint en On the Waterfront— ¿es un hombre o una mujer en esa escena? Bueno, en un tiempo de fundamentalismo y literalismo, es un hombre. Pero esa no es necesariamente la manera en que las cosas son. O cuando vemos a Dylan en Don’t Look Back en el Royal Albert Hall— cosas como la edad y el género simplemente no computan. Pero ese modo seco de ver— donde nuestra identidad superficial es tan definitoria— eso es un asunto capital. Mientras nos agarremos a nuestra identidad superficial, vamos a estar algo asustados y tensos. Y asustados y tensos es caldo de cultivo para consumidores leales, domesticados. Alguien que escribió muy elocuentemente sobre todo esto es Rita M. Gross, una genial escritora feminista. Construye un argumento bastante convincente de que el camino para terminar con la dominación patriarcal tiene que conducirnos más allá del género.

Cuando tenía ocho años fui a una clase de interpretación en HB Studio. Fue cosa de un fin de semana, la mayoría improvisación. Me encantó. Luego, alrededor de Navidad, recibí una llamada. Querían que leyese una cosa de Navidad con Herbert Berghof mismo. Solo yo y el viejo Herbert en un escenario frente a cientos de personas. Nunca volví a esa clase, nunca actué de nuevo. Solo quería hacerlo por diversión, no por la multitud. Creo que eso está bien. Hay tanto énfasis ahora en ser visto. Todo tiene que estar validado siendo visto. Está el miedo de quedar olvidado. O de desvanecerse. Pero gran parte del tiempo, cuanto más visible es algo, más realmente se desvanece. Por ejemplo, ¿cuándo fue la última vez que alguien vio verdaderamente a la Mona Lisa?

En retrospectiva, gasté un montón de tiempo intentando convertir a las estrellas de cine en monjes. A veces bastante literalmente. Escribí un guion sobre Maura O’Halloran, llamado Mu. Maura era una joven mujer irlandesa que fue a un templo en Japón y meditó noche y día. Tuvo algunas experiencias iluminadoras y justo después de eso, murió. Con veintisiete años en un accidente de autobús en Tailandia. De todos modos, durante años me toparía o hablaría por teléfono con varias actrices, jóvenes estrellas de cine, y charlaríamos a propósito de Maura O’Halloran. Había mucha confusión y miedo alrededor del proyecto. Recuerdo a una actriz diciéndome– “No lo entiendo, ¿cómo el viejo maestro japonés Zen supo que Maura sería capaz de hacer la práctica rigurosa con todos esos hombres japoneses?” Y yo decía– “es como un casting. Por ejemplo, cuando un director de casting te escoge en tu primer papel”. Recuerdo estar hablando a un agente en la CAA que intentaba que su cliente no interpretase a Maura, incluso aunque ella lo quisiese. Yo decía– “Escucha, ella va a ir a Japón, aprenderá algo de japonés, y se afeitará la cabeza– solamente afeitarse la cabeza le hará ganar premios de interpretación”. Era como un mal vendedor de coches. Y el agente de la CAA: “El único proyecto para el que va a afeitarse la cabeza es Daughter of Kojak”. La mayoría de las películas, en esencia, son hechas para reafirmar nuestro delirio de tener una identidad permanente, sólida. Hollywood está establecido para perpetuar ese mito y condicionamiento. Pero esta era una película donde el personaje principal se da cuenta de que en verdad no tiene identidad. Era algo difícil de vender. Finalmente, después de años de estar hablando con varias estrellas de cine sobre interpretar a Maura, me di cuenta de que realmente estaba intentando convencer a la estrella de cine dentro de mí para convertirse en un monje. Y por estrella de cine dentro de mí simplemente me refiero a mi ego. Fue un alivio real cuando me di cuenta de que de hecho no tenía que alistar a una actriz famosa para hacer este trabajo. No era necesario. Pero sí tuve que sentarme en un zafu y cruzar mis piernas y respirar. Eso fue necesario para mí, y sigue siéndolo.

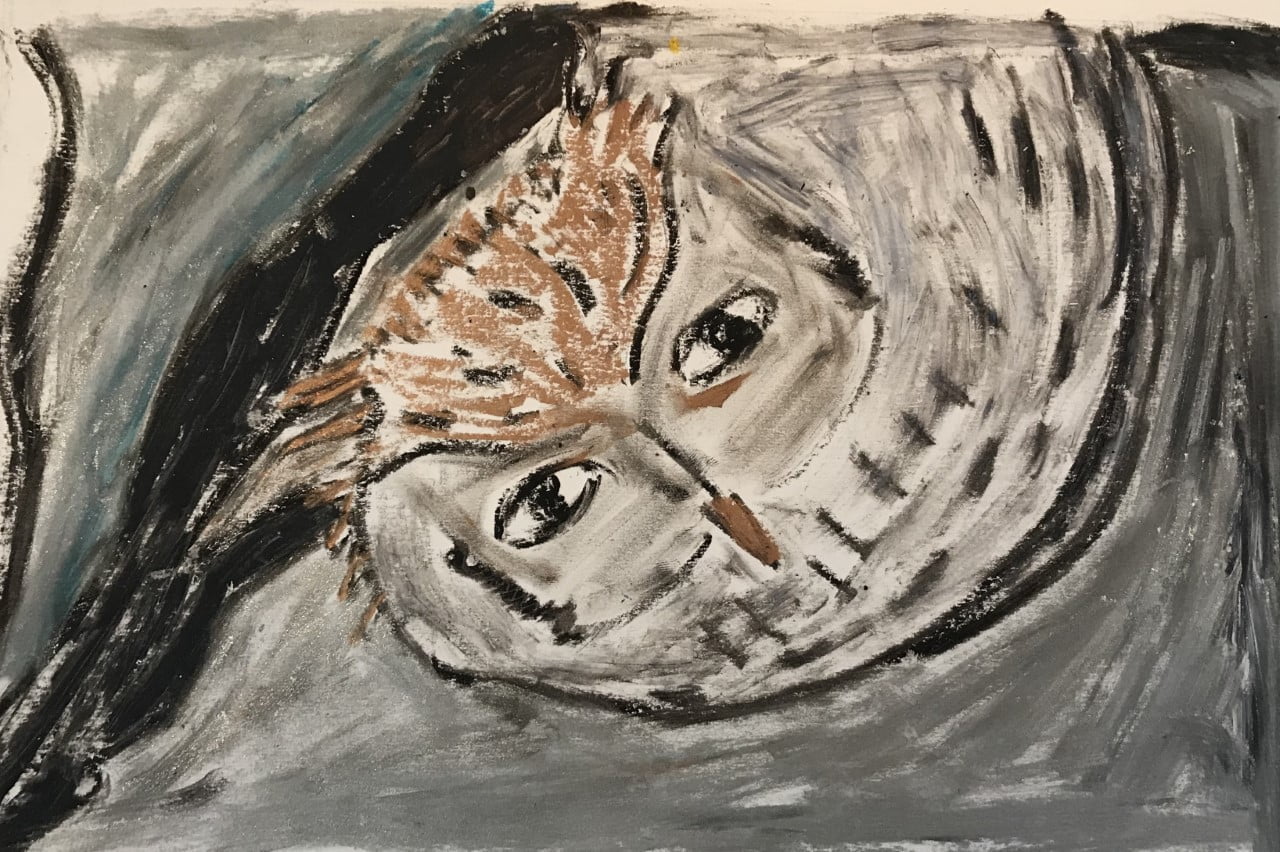

Hay muchos guiones sentados en mi estantería, como le pasa a cualquiera que ha estado escribiendo guiones durante veinte años. Uno de ellos trata de Philip Guston, llamado Hoods. Es sobre la época en la que Guston pasó de la pintura expresionista abstracta a la pintura figurativa y cómo el mundo del arte lo condenó al ostracismo. El show de la Marlborough Gallery. Todavía tengo la crítica feroz para The New York Times de Hilton Kramer, titulada A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum, fijada en mi escritorio. Guston estaba adelantado al Times. Pienso que Hilton Kramer probablemente se sintió amenazado y a la defensiva e incluso algo celoso. El nuevo trabajo de Guston era tan libre y encrespado y poco culto. Pero ¿qué es “poco culto”? Las tiras cómicas de Krazy Kat de George Herriman tienen más sentimiento e inteligencia que muchas de las novelas ganadoras del Premio Pulitzer. A corto plazo, la crítica de Kramer hirió la carrera de Guston. Pero a largo plazo, solo reveló a Kramer como un protector poderoso del statu quo.

Hay un guion acerca de ratas tomando Nueva York llamado Rats! Rats! Rats! Sabéis, como ratas gigantes, del tamaño de elefantes, deambulando por Macy’s. Hay un remake de la película de Rowdy Herrington, Jack’s Back. Todo tipo de guiones. Uno de mis favoritos es algo que escribí para que Andy Dick y Katt Williams lo protagonizasen. Se llama Brother from Another Mother. Su padre fallece y les deja un diner en un vecindario duro de Philly. Andy Dick y Katt Williams tienen que reunirse y proteger el diner. Es una película completamente inasegurable, pero en ocasiones simplemente tienes que escribir la cosa.

Recientemente escribí una descripción detallada/declaración de principios para un documental acerca del grande del béisbol, Eric Davis. Davis es un hombre negro de South Central. Llevé este proyecto a un director y productor afroamericano. Luego me disolví en el fondo– una persona blanca siendo la fuente creativa podría ser problemático para algunos. Demonios, The New York Times recientemente publicó un artículo diciendo que cualquier artista que se desplaza fuera de su propia cultura está cometiendo un acto de minstrelsy. Pero siento que es posible caminar en los zapatos de otros. No solo posible, sino necesario. Si no caminamos en los zapatos de otros, estamos destinados a caminar con miedo.

A veces es saludable no estar acreditado. Ser un escritor fantasma. Lo que queramos ser o lo que queramos tener, realmente no es posible porque todo está cambiando siempre. Es como agarrar el agua. Pero aun así queremos ser embaucados. Queremos ser engañados— “¡oh, ahí está mi nombre en los créditos!” O, “oh— me han publicado, eso debe significar algo”. O “oh, recibí este premio”. Genial, ¿ahora qué? Eventualmente renunciamos a obtener algo o convertirnos en algo. Nada puede ser nuestro. Ni siquiera nuestro propio nombre. Ni siquiera nuestra propia cara.

En términos del estado del cine independiente hoy, no tengo ni idea. Como cada vez se crea más y más contenido, es difícil saber siquiera de lo que estamos hablando. Uno no puede caminar por la calle sin ver cincuenta películas siendo rodadas en iPhone. Si tanta gente está rodando sus películas todo el tiempo, y editando sus películas todo el tiempo, es probablemente un buen momento para retornar a hacer cosas con nuestras manos. O para hacer teatro. Los nativos americanos eran supuestamente naif cuando pensaron que las cámaras faltaban al respeto al mundo espiritual y robaban alma. Pero quizá estaban teniendo una visión de nuestra desaparición futura. Cómo las cámaras nos consumirían. Cómo eventualmente mutilaríamos nuestros cuerpos con el fin de aparecer de una determinada manera para la cámara. En ese contexto, incluso hablar de películas ahora parece algo grotesco. Realmente nos estamos matando a nosotros mismos con cámaras en este momento. Entiendo que en algunos casos, como con las body cams de la policía, las cámaras realmente salvan vidas. Pero en su mayor parte parece que nuestra obsesión con grabarlo todo solo nos conduce más lejos de la realidad. Para mí es un buen momento para preguntar— ¿qué demonios son las películas de todos modos?

Ahora, si algún estudio se acercase a mí y me dijese “nos gustaría que dirigiese Doppelgänger, Poltergeist”, ¿me pondría tan condenadamente filosófico? Quién sabe. Creo que sí, no obstante. Genuinamente estoy quemado de dirigir. Y no soy muy bueno lidiando con la jerarquía. ¿Quién es el director, quién está arriba en la hoja de rodaje, quién tiene qué crédito de productor… a quién coño le importa? Ves las mismas cosas a veces con la religión. La gente empieza a tragarse lo de la jerarquía. Imagina lo que diría San Francisco de Asís si se fuese a reunir con el Papa Francisco en la Ciudad del Vaticano. Podría decir —“ey, Papa, tomemos un paseo en el bosque, saquémosle de todo este blanco”. Al mismo tiempo, entiendo, cuando alguien está yendo de set a set, año tras año, su posición se convierte en real para ellos. Incluso en un set pequeñito. Por eso intento tener perros en mis películas cuando es posible. Cuando hay un cachorro de labrador corriendo por el set y lamiendo a todos se hace difícil tomarse las cosas tontas seriamente.

Con The Man in The Woods, en realidad opté por no enviarla a los críticos cuando se me fue dada la opción. La pandemia justo había empezado y sentí que sería de mal gusto el simple hecho de lanzar una película, mucho menos promocionarla. El compromiso era lanzarla sin fanfarria, sin crítica, sin tráiler, sin nada… A veces amigos me pasan cosas diciendo cuán trágicamente poco vistas están mis películas, pero no es trágico para mí. Si lo fuese, habría trabajado más con las agencias de relaciones públicas. Y generalmente habría sido más aquiescente con mis agentes y mánagers. Pienso que mis películas han sido mal publicitadas por los distribuidores, pero eso también es parte del proceso. Hice estos poemas de comic book de bolsillo de 80 minutos con los actores con los que quería hacerlas y… ya sabéis, si más gente las viese, quizá habría sido más fácil hacer otras cosas, pero de nuevo, quizá no. Cuando miro a Francis Ford Coppola, Orson Welles, Val Lewton, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Sam Fuller, Hal Ashby, Nicholas Ray y todos los otros maravillosos cineastas que han luchado para conseguir que se hiciesen sus películas… Quiero decir, ¿quién soy yo para quejarme? Si quieres hacer un trabajo singular, personal, desde el corazón, no puedes esperar tener la alfombra roja desenrollada para ti. El sistema realmente está vigilando a ver si te vas a congraciar o no.

No he visto muchas películas nuevas. No sigo realmente las películas de Marvel o A24. Pero una película que vi recientemente por primera vez fue Mr. Smith Goes To Washington de Frank Capra. Cuando Claude Rains gritó “¡Expulsadme! ¡No estoy hecho para ser senador! ¡Expulsadme! ¡No soy apto para el cargo! ¡No soy apto para cualquier sitio de honor o confianza! ¡Expulsadme!”– aquello me dejó impresionado. Fue como oír una campana de expiación. En vez de la virtud señalando o escurriéndose del lado del marginado o retorciendo la historia para hacerse parecer a sí misma inocente, aquí había alguien que estaba diciendo– ¡soy yo! Soy responsable de toda esta catástrofe. Es mi codicia, y mi corrupción, y mi oscuridad. En medio de todo el ruido de fondo, sonó a verdad.

NUESTRAS PREGUNTAS ORIGINALES

1. Algo que nos obsesiona de tu obra, en lo que no paramos de dar vueltas desde que la descubrimos en enero de 2022, es la presencia interna de tus ansiedades, luchas, guerras mentales. En una entrevista, dejabas entrever que el concepto de auteur, así traspasado por los jóvenes turcos de Cahiers du cinéma al mundo del cine, podía parecer hoy en día superado, aludiendo a que Sidney Lumet lo categorizaba de pretencioso. Tú argumentabas que quizá sea así, pero que no hay nada como contemplar un filme cuya visión no haya sido alterada, mancillada, intoxicada por fuerzas ajenas. Sirva esto como pequeña justificación a lo que resta de pregunta. Atendiendo a los diferentes pasos que has tomado en tu carrera, a tu evolución como cineasta, podemos ver diferentes tonalidades, etapas: el niño neoyorquino leyendo una y otra vez Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas de Hunter S. Thompson, creyendo que no tiene nada que ver con Thich Nhat Hanh y su Plum Village. Poco a poco, la necesidad de canalizar, reconciliar esa ira Manhattan con tus crecientes preocupaciones, con las prácticas Zen, y cómo la cultura beat poco a poco fue coagulando, soltando sus amarras, en tus nuevas prácticas, el poco problema que te fue suponiendo con el tiempo relacionar las vivencias de Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac o incluso Bob Dylan con el bodhisattva. En tus filmes existen estas diatribas belicosas, a medio camino entre la promesa de un respiro que quizá emerja en un pequeño gesto postrero, y preferimos no llamarlas dualidades. Las dos fuerzas que tiran de Hopper en The Phenom (2016), su padre y el Dr. Mobley, dos maneras distintas de entender la ética darwinista del deporte en EUA, también una suerte de pedagogía encarnada en el personaje de Giamatti. Encontramos esto también con Ellen en Glass Chin (2014), representada por tu habitual compañera de trabajo Marin Ireland, intentando como quien no quiere la cosa, pero sin ninguna doblez, comunicar algo a Bud, boxeador que no tiene tiempo, o más bien paciencia, para verdaderamente aprender a generar calor en el frío ─y no, no se trataba solo de una técnica respiratoria─. Manhattan acechando a Nueva Jersey, Los Ángeles cerniéndose sobre John Rosow, el montículo que aprisiona a Hopper.

Tras este rodeo, simplemente nos gustaría entender, en la medida de lo posible, de qué manera trabajar en el cine, establecer estos escenarios, supone también para ti un honesto ajuste de cuentas, contigo en primer lugar, con el mundo y su arrollador aceleracionismo y su inmoralidad luego. En medio de todo esto, no pueden faltar tus referentes, quizá víctimas o combatientes de luchas pasadas, como esos jugadores de béisbol que jalonan tus filmes, el recuerdo del fútbol americano en The Man in the Woods [2020] (todavía no logramos distinguir quién es el jugador que remata los créditos de dicho filme), viejos y geniales jazzmen como Fats Navarro, nombres que se sueltan y alumbran algo el tablero, como Paul Robeson. Nosotros te consideramos un cineasta cuya moral se puede ver derramada en cada plano, consciente o inconscientemente, langiano como solo un americano que ha vivido en Greenwich Village puede serlo. Nos da la sensación de que estás en el espectro contrario de la broma-codazo, de la risa cómplice, tu seriedad permea tus filmes sin por ello arrebatarles el mencionado calor. Lo dicho, y retornando a la cuestión del autor, ¿de qué manera todos estos referentes, mundología y epistemología personal se imbrican en la práctica diaria, tan coyuntural, de hacer cine?

2. Te hemos leído en varias declaraciones mostrándote muy crítico, combativo, incluso cabreado, sobre el estado del cine “independiente” estadounidense. Son unos cuantos los problemas que identificas: en primer lugar, el acomplejamiento de algunos cineastas noveles que asumen que deben realizar un filme indie para luego acabar haciendo trabajos de estudio ─como quien concibe un cortometraje como trampolín para acabar realizando un “largo”─, luego, percibes un anquilosamiento formal de los filmes entendidos como “independientes”, cierto estilo a imitar, por ejemplo el preciosismo fetichista o la frialdad de la Criterion Collection, también sueles enervarte con aquellos productos que por motivos industriales y de distribución interesa tildar de indies, cuando en realidad ocultan en su concepción procesos formulaicos, y en los peores casos, varios test screenings. En definitiva, filmes que parecen maquetados por el propio Festival de Sundance. Con estas palabras, recuperamos los diagnósticos que hacías más de diez años atrás. Así que, ¿cómo ves hoy el estado del cine independiente estadounidense? ¿Podrías hablarnos de cineastas o filmes que, en los últimos tiempos, te hayan interesado como ejemplos de cine indie, es decir, tal como este fue concebido a finales de los cincuenta, principios de los sesenta, como una forma emancipada que ataca desde el exterior para combatir a los estudios?

3. Durante el transcurso de tu filmografía has bregado por dignificar un tipo de pátina digital muy lejos de aquellos filmes que solemos ver realizados con este tipo de especificaciones técnicas. Empezaste tu carrera atreviéndote a filmar Bringing Rain (2003) en formato DV, con una Ikegami, Sparrows Dance (2012), Glass Chin y The Phenom son filmes realizados en Red Digital, mientras que para The Man in the Woods te pasaste a una ARRI. El pequeño proyecto que ideaste en 2014 junto a Liza Weil ─The Situation is Liquid─, con un presupuesto de no mucho más de 3000 $, optaste por abordarlo con una Blackmagic Pocket. Aunque cada vez más en boga en la industria cinematográfica, este es un equipo que solemos encontrar en producciones destinadas al streaming, que puede encontrarse en escuelas de cine, usualmente utilizado de forma poco consecuente, aberrante e incluso como una imagen de marca. En tu caso, admiramos la sutil posproducción que logras imprimir en tus filmes digitales. ¿Qué puedes decirnos del modo en que te sirves de estos instrumentos y cómo afectan estos procederes digitales a nivel presupuestario, de planificación, rodaje y posproducción de tus filmes?

4. Has tenido relación a lo largo de tu carrera con tres directores de fotografía diferentes. Yaron Orbach encargándose de dicha labor en Bringing Rain y Neal Cassady (2007), luego ocupando la zona troncal de tu trayectoria, hallamos a Ryan Samul, con el que compartiste trabajo en The Missing Person (2009), Sparrows Dance, Glass Chin y The Phenom, Robbie Renfrow en The Situation Is Liquid, para terminar con Nick Matthews en The Man in the Woods. Nos llama la atención el incremento de una mayor rigidez, sin estar reñida con la respiración de los planos ni la sensación de espontaneidad que tiene la recepción espectatorial ante el desarrollo dramático tan concomitante con el despliegue del découpage. A este respecto, no deja de sorprendernos cómo un filme tan preparado de antemano en su sucesión de planos como es Glass Chin se descubra tan desenvuelto, o que los planos-búnker de Sparrows Dance comiencen a liberar una suerte de energía expansiva a medida que avanza la relación entre Wes y la Mujer en el Apartamento, por muy atada que pueda estar la cámara al trípode; paradójicamente, ocurre lo contrario que en tantos filmes saneados por el Sundance de hoy ─en el que parece imposible encontrar revulsivos como High Art (Lisa Cholodenko, 1998) o What Happened Was… (Tom Noonan, 1993)─, donde esa cámara en mano termina por aprisionar cualquier atisbo de sentimiento sincero. Sin embargo, en The Phenom, encontramos una vertiente ya bastante alejada de la capacidad adaptativa del montaje de The Missing Person, sirviendo el plano como una especie de lente macroscópica que avanza con cautela, control y seguridad, permitiéndonos observar la situación con una posición que si llamamos distanciada, únicamente lo hacemos en el sentido de un Philip Marlowe inquisidor. Este control del plano, su duración alargada, y el juego con el zoom in milimétrico, llega a su tope en The Man in the Woods, donde por asfixia espacial se abren verdaderas brechas, como la irrupción del color, o ese flashback a intermitencias donde Paula revisa su trabajo sobre Red Damon.

¿Podrías desarrollar todo esto de la manera en la que te sientas más cómodo, intentando proporcionarnos una visión de conjunto sobre cómo ha evolucionado tu relación con los DPs y de qué manera estos han contribuido a moldear con cada película una relación más estable o afianzada del acto de filmar?

5. The Missing Person es tu filme con más tránsito, escenarios, movimientos locales. En los alojamientos, vehículos, en el asfalto y la tierra que pisotea Rosow resiguiendo la pista de Harold Fullmer, su deambulamiento mental encuentra una natural concomitancia. Merced sus recurrentes trayectos en taxi, por ejemplo, podremos identificar, en la sonrisa que se le dibuja a Rosow cuando por fin se suba al último ─el conductor negligente con el pitillo, la licencia desaliñada y caricaturizada, etc.─, que el protagonista guardaba en su fuero interno un acondicionamiento algo punk, y para comprenderlo, nos hicieron falta todos esos viajes donde se le quejaran de fumar los chóferes anteriores.

Cuando se estrenó la película, referiste cierto estrés en la producción, falta de tiempo, las dificultades inherentes a condensar la energía en el set cuando las prisas por cambiar de espacio acechaban; todo ello, sin embargo, por virtud de haberte sabido rodear de un equipo que no desfallece, llegó a buen puerto, en gran medida gracias al tesón del inagotable Michael Shannon. A partir de este filme, dices haber aprendido definitivamente que el modo en que más disfrutas y te sientes más cómodo haciendo cine es abrazando una tendencia dirigida a hacer decrecer los elementos a controlar. Aun pensando que The Missing Person es uno de tus mejores filmes, llegamos a la conclusión de que a partir de este tu cine ha dado un paso adelante en cuanto a conceptualización, en el buen sentido de la palabra, y que las guerras mentales de los personajes que llevas proponiendo a lo largo de toda tu filmografía han adquirido una concreción, un nivel de condensación, muy características. También has afirmado que, al menos según tu método de trabajo, es erróneo pensar que tus filmes surgen primero como historias, que eres un cineasta, no un storyteller. ¿Puedes explayarte en cómo se conecta ese aumento de la conceptualización con tu convicción de que tus filmes surgen de cierto estado de ánimo, atmósfera, o incluso de una imagen? ¿Cómo afecta este planteamiento al modo en que has ido financiando tus proyectos?

6. En tus filmes, salta a la vista el relativo aislamiento de los personajes; suelen constituir un islote apartado respecto a las multitudes, estas últimas, rara vez representadas ─las noches deshabitadas de Glass Chin─, fantasmalmente ausentes ─el mundo exterior en Sparrows Dance─, o conformando un bloque hostil o indiferente… que se opone al individuo ─en The Phenom, la nube de periodistas que atosiga a Hopper, los clientes de la cafetería donde conversa con Dorothy, mudos, al igual que los comensales del vagón-comedor en The Missing Person─. A veces nos invade la sensación de que el pueblo estadounidense se encuentra al completo encerrado en sus casas drogándose con algún sucedáneo, agorafóbico, perdido, siguiendo por televisión cualquier deporte o espectáculo televisivo. Percibimos también una ausencia de barullo sonoro, contagio o complemento de la composición de los encuadres, un silencio esencial que rodea a los personajes y los hace confrontarse más directamente con ellos mismos, sus pronunciamientos y los de los demás. ¿Podrías hablarnos un poco de la visión del mundo que sustenta estas decisiones formales?

7. No hace falta ser un gran cinéfilo para ser un gran cineasta, sin embargo, tenemos constancia de que tu trayectoria vital está marcada por visionados, filmes, que se imbricaron en tu existencia indeleblemente. Cuando tenías seis años, durante tu convalecencia por la varicela, presenciaste On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) por televisión una y otra vez, como un sueño hipnótico, y no has dejado de volver a ella. Más tarde, tu fiebre cinéfila coincidió con un gran momento del cine independiente estadounidense, hacia finales de los noventa, donde podemos encontrar filmes que te encandilaron como The Whole Wide World (Dan Ireland, 1996), Lawn Dogs (John Duigan, 1997) o Whatever (1998), filme de Susan Skoog el cual te hizo prendarte de la actuación sin fingimientos de Liza Weil. Por otro lado, lamentas que directores independientes que se embarcan por primera vez en dirigir acaben redirigiendo sus proyectos formales hacia cuatro estilemas mal digeridos de John Cassavetes, Woody Allen o Jean-Luc Godard, sin haberse dado el espacio suficiente para rumiar sus referencias. ¿Cómo ves actualmente la salud cinéfila de los nuevos directores? ¿Puedes hablarnos de cineastas o filmes que hayan sido importantes para ti, que como una fuerza moral te hayan acompañado, formado, instruido, a lo largo de tu vida?

8. Del mismo modo que On the Waterfront no es un filme sobre el boxeo, nos resistimos, como tú, a pensar que Glass Chin lo sea, o que The Phenom trate directamente sobre el béisbol. No obstante, percibimos una ligazón fundamental entre estos dos filmes, en tu preocupación por unos protagonistas cuyo sometimiento espiritual obedece a cierta reglamentación deportiva, una severidad institucional con raíces culturales, tentáculos económicos, aspiraciones publicitarias, jaulas mentales prescriptivas que les impiden, por ejemplo, meditar los sabios consejos de sus compañeras. A veces, tanto Bud como Hopper dan la sensación de repetir como una letanía, con dudosa convicción, una visión del mundo amañada que a las claras les jugará a la contra. Como una insistente piedra en el camino de un país que intenta borrar, encubrir, sus brutalidades y genocidios, también en The Man in the Woods encontramos ese récord deportivo perpetrado por un nativo americano que se resiste a ser soterrado en la Historia de la nación. Y ya que citábamos a los beats, recordemos al Kerouac adolescente queriendo dedicarse al periodismo deportivo, redactando privadamente sus ligas de fantasy baseball, o en tu filme Neal Cassady, cuando le reprocha a Neal estar soltando su «young, damn football talk», y Neal insinúa que quizá solo le interesa su compañía para así conseguir material para sus escritos. ¿Qué es lo que te interesa de estos caracteres ─como Ellen le reprocha a Bud─ que achacan un condicionamiento ESPN en su visión del mundo? ¿Qué conexiones tienen para ti estas rigideces mentales inculcadas con las problemáticas psíquicas, históricas, de Norteamérica?

9. Marin Ireland hablaba con motivo de Sparrows Dance de tu querencia por usar actores que tuvieran un cierto background teatral y relacionaba esto con el gusto por la toma de larga duración, bastante translúcido en el filme mencionado. Sin embargo, esto no conculca la utilización de planos que duran escasos segundos, ni es un sistema que apliques al proyecto formal del filme. A los actores con los que trabajas, y no solo por lo que leímos a Marin, sino por nuestra propia sensación, parece excitarles esta manera de trabajar. Te decimos sin pizca de hipérbole que ver Glass Chin nos redescubrió salvajemente a Corey Stoll, sus réplicas, reacciones en planos frontales, esa personalidad dicharachera que domina al principio del filme para luego ir desgarrando aquellos condicionantes que le hacen inseguro, condenado a la retaguardia, viéndose encerrado entre sus aspiraciones y su moral. Su espontaneidad nos regala la vista y los oídos. Volvemos a encontrarnos con una actuación masculina en el cine americano que nos embelesa. Viendo Lawn Dogs, anteriormente mencionada, pudimos sentir algo similar en lo desbocado y apasionado de Sam Rockwell y Mischa Barton ─qué lejos de la pose, de lo relamido, queda su baile al son de Dancing in the Dark de Bruce Springsteen, una sinceridad americana dispuesta a arramblar con todo─. En fin, nos congratula que ese sentimiento al ver a Liza Weil en el filme de Skoog ahora lo tengamos nosotros con tus filmes, con Corey Stoll paseando con Kelly Lynch en Noche Buena mientras el mundo está a punto de venírsele abajo.

¿Cómo es tu relación con los actores en el set en el día a día? A pesar de su fama, has logrado sacar una verdad infalible de Michael Shannon, Paul Sparks, Stoll o numerosos intérpretes que nos dejamos; muchos directores con más pedigrí de pandereta no lo consiguen. En cambio, tú pareces haber desarrollado un método maleable en el que las ocasionales tomas largas, cambiantes o estáticas, los planos de reacción, la posibilidad de dejar a una actriz mirar al que habla o enunciar ella misma separada por el encuadre sus divagaciones sentimentales, conforman un campo con posibilidades inacabables. Nos gustaría que te explayaras sobre todo esto, simplificando, el continuo aprendizaje de cómo se trabaja con actores en un set, pero también antes de llegar a este, y el grado necesario de libertad que se les debe otorgar para que no solo, como tú dirías, sepan llorar bien, o pongan acentos con precisión de superdotados, sino para que contengan una verdad irrompible.

10. Hemos mencionado a Springsteen. Nos toca preguntarte por algo que lo incumbe ─aunque nos intrigan y nos hacen muchísima gracia las referencias jocosas que introduces con respecto a su persona en The Missing Person y Glass Chin─. Hubo un tema suyo, American Skin (41 Shots), que sabemos de particular importancia en tu viaje espiritual. Dicho tema concernía al brutal asesinato de Amadou Diallo por cuatro agentes de policía. La reverenda Pat Enkyo O’Hara sacó el tema en una charla Dharma, lo cual te dejó verdaderamente sorprendido y supuso el principio de una conmensuración, que te llevó a comprender que el budismo no se trataba de renunciar o dejar de lado la cultura en la que habías crecido ni en dejar de ser americano. Esto va en consonancia con la mayor asistencia a los zendos, la transformación de una rama del Zen disciplinada en América que evoluciona desde su aparición como fuerza contracultural a motivo religioso que se extiende y atrae a cada vez más devotos, inspirados por la cada vez mayor heterogeneidad de la propuesta, un proceso donde pierden importancia las jerarquizaciones del pasado. La charla particular con el hombre del bosque que necesita Bud cuando mira en un escaparate unos ejemplares de un libro de Pat Enkyo O’Hara, la que seguramente requerirían cantidad de personajes a la deriva en tus filmes. Sin embargo, tú la has tenido, en cierto sentido, y nos gustaría comprender un poco cómo evoluciona tu trayectoria en el mundo del budismo, desde Nepal a los programas Dharma dentro de centros carcelarios, pasando por la incorporación de la mitología americana, y culminando su inclusión en tu escritura, tanto literaria como fílmica. ¿De qué modo la práctica Zen ha influenciado tu manera de enfrentarte a un filme?

11. Terminamos esta entrevista con tu último filme hasta el momento, The Man in the Woods, un guion que, si no nos equivocamos, ya tenías terminado (más allá de futuras revisiones y reescrituras) en el año 2015, y al que tú mismo te referiste aquel año como quizá el único guion que hubieses escrito que fuese completamente sólido. Por lo tanto, hablamos de un proyecto que llevaba rondando tu mente años. El cambio ya mencionado de DP nos resulta significativo y, aun así, tu proyecto formal semeja una evolución clara del The Phenom, con ese énfasis secuencial en la construcción de las escenas, la vital importancia de los diálogos expansivos de a dos, donde una sutil abstracción dispara al filme a muchísimos lugares y momentos de la historia americana, como ocurre con, precisamente, un relato que creemos te gustaría adaptar, Doppelgänger, Poltergeist de Denis Johnson. Más que una reconstrucción de época apelando a la nostalgia en un sentido unívoco, un reto para el espectador. Las referencias culturales desbordan en su especificidad, la jerga es más compleja que nunca. Y sin embargo tu discurso es ardientemente político, un rodeo nocturno por diversos traumas abiertos, culpas escoradas, curaciones de última hora, dudosas logias masónicas, la obsesión con un récord de yardas, y aquellos manchados, victimizados, marginados, enloquecidos, por ese círculo de paranoia. Nos es inevitable establecer una relación natural entre tu último filme y el mencionado relato de Johnson. Por encima de todo, el casi total silencio crítico ante The Man in the Woods, la espeluznante falta de información sobre el filme, nos fastidian de verdad. ¿Nos puedes hablar de la concepción, rodaje, montaje y todo lo que vino después, una vez completado el filme, en tu vida a nivel de recepción ante la obra? ¿De qué modo ha sido inspiracional el trabajo de Denis Johnson en tu práctica artística?

Esperamos que siga en tu mente la adaptación de ese relato, o por lo menos cualquier otro proyecto, y que tus ánimos no decaigan por la situación actual. Como pudo presenciar Robert Grainier en Train Dreams, quizá esté próximo el momento en el que todo de pronto se vuelva negro y esta época desaparezca para siempre.

Un gran abrazo, Noah. Tus filmes nos han acompañado y trabado sincera amistad con nosotros. Toda la suerte del mundo.