ESPECIAL NOAH BUSCHEL

Glass Chin (2014)

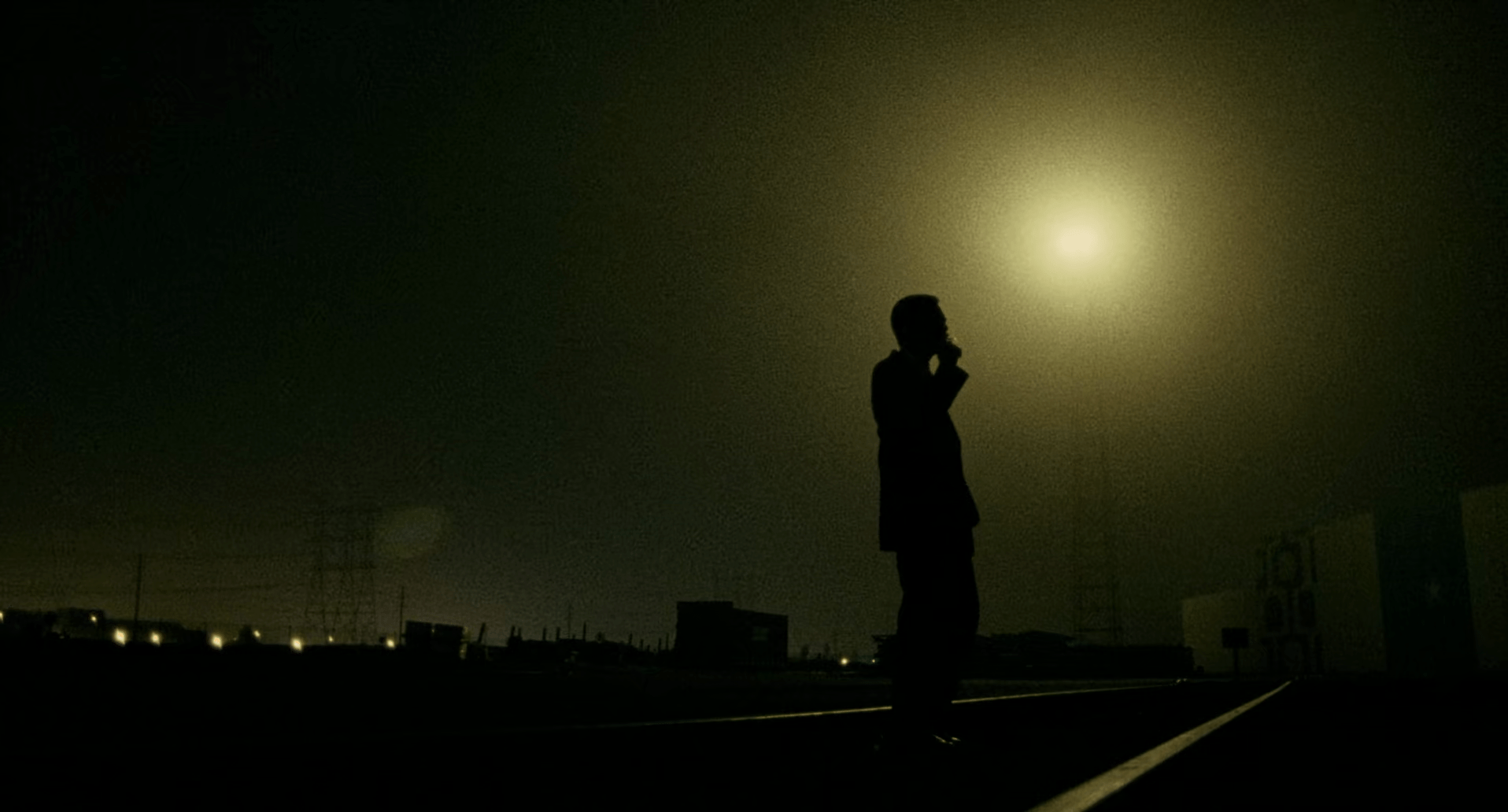

The Man in the Woods (2020)

En el sendero, fuera de la ruta; por Gary Snyder

Interview – Noah Buschel

Entrevista – Noah Buschel

Last January, we discovered the films of Noah Buschel. In addition to the feeling of euphoria that is transmitted to the spectator by an œuvre that enthuses him, at that time we were puzzled by the almost total lack of critical discourse around the films of the filmmaker in question. Beyond writing a few texts trying to reflect on his body of work, we felt that we should contact Noah and give him the opportunity to speak at length. When contact was established, we discovered an attentive, generous person, willing to solve any kind of doubt and even to offer us extra attention. We hope that our questions serve as a little recollection of the filmmaker’s journey. Above all, our enthusiasm lies in the fact of being able to share Noah’s answer, a unitary reply to our long questions that sheds light on his own œuvre and the present we live in, giving it a mirror to look into. At the end you will find our original questions.

NOAH BUSCHEL’S ANSWER

At first I did it because it seemed beautiful, shooting deserted places. We were making this boarding school movie and the school was shut down for the summer. Day after day I found myself sheepishly turning away extras. I’d have to whisper to the A.D.– ‘sorry, can you have those kids go home?’ It was more interesting to see the actors walking through empty halls and gymnasiums and locker rooms. In the screenplay, the students were kind of like phantoms wandering through the bardo. To shoot the school as a ghost town made sense. That’s probably how I would describe high school in general– phantoms wandering through the bardo, in between bodies, in between lives.

There’s not a lot of drama in my movies. But if there is drama, I think it comes from the loneliness. And by that I mean– the loneliness is romantic, and it’s pretty, and it’s cool, and it’s maybe even peaceful and comfortable. But it is also threatening. The Christmas lights outside a vacant house. A train with almost no one on it. A desolate street. The characters in my movies are always on the verge of being swallowed up by this loneliness. The seemingly innocent 1950’s American style that I establish in all these movies— neon buzzing, snow falling on a diner, a shiny red Coca-Cola truck– that is the seductive quality of loneliness. It seems so romantic at first. When you’re seventeen and smoking a cigarette and walking down Broadway at 3 AM. Even insomnia and insanity seem glamorous at the beginning. But I think my movies are really anti-romance. They have all these classic American tropes, but in the end, the love that saves us is more mundane and practical than that. Like in Sparrows Dance. The love that really supports her getting outside of herself is not starry-eyed at all. It’s the kind of love that stops suicide. It’s an ordinary love that has its feet firmly planted on the ground. It’s a love that wakes one up. So, my movies, they are meant to feel like timeless dreams, like floating in a hot bath. But in the end, they say– hey, wake up. Don’t drown in the American Dream. Don’t fall for it. Don’t be cool. Open your heart. It’s a matter of life and death. Really I’m trying to wake myself up.

Seeing our own shadow is the work, I figure. Making the darkness conscious. It’s the work of a filmmaker, of an actor, of a meditator, of a human being. If we even glimpse our own shadow, it becomes more difficult to go around blaming the government, or blaming Putin, or blaming an ex-lover, or blaming an old friend who we feel betrayed us, or blaming the NRA, or blaming Hollywood, or blaming Cancel Culture, or blaming the Internet… It’s empowering to stop finger-pointing. Everything that we encounter is our own mind, so finger-pointing is kind of absurd. But because we are so precious to ourselves, we like to pretend that the dark stuff has nothing to do with us. And then we can return to our self-righteous routine. It’s like walking around going—’that drunken homeless person is not me, that plastic debutante is not me, that steaming pile of dog shit is not me, that violent outburst on the corner is not me… oh, there’s a splendiferous rose in the flower shop window— that’s me! I’m gonna take a picture of the rose and post it on Instagram. And really base my identity around it.’ Or ‘oh, there’s a photo of Martin Luther King in the book store window— that’s me. And there’s a photo of Trump on the cover of the newspaper— that’s not me.’ When we deny our own shadow, that makes us very fragile. Like a china doll, we become easily broken. Nobody means to break us, it’s just what happens when we cherish ourselves so much.

For a long time I tried to separate the good and the bad, placing the saint in one corner and the demon in the other. I went through life trying to pick and choose who I was connected to and who I wasn’t connected to. But in doing that, I just ended up chaining myself to that which I denied. Letting go isn’t a negation, it’s an affirmation, a turning towards. The more enemies we block, and the more scapegoats we tweet about— the less we know who we are. It seems to me. We end up living our lives based on the delusion of a projection. You could call that projection a movie, I guess. In that movie, all of the disowned parts of our being emerge as the other. And we carry this narrative around that we are separate. Which leads to two ways of reacting to everything. That’s nice, I want it. That’s not nice, I don’t want it. Everyone and everything is objectified, to some extent, if we don’t realize they are us.

Anytime an entire industry is set up around recording impermanence, there are going to be a lot of scared people who flock. People who don’t want to see that basically this is all completely impermanent and empty. You can hear the desperation in the voices of some film preservationists. But movies aren’t forever. Even on the internet, which is also not forever. Eventually it will all vanish. Maybe Scorsese will be shown on Mars in a thousand years to a crowd of half humans/half robots, but that only means his movie had a slightly longer run. Eventually even his run will be done.

I partially went into movies because of my own fear of impermanence. It’s not black or white– I was also inspired by many filmmakers and actors when I was younger and have a genuine love of movies. And of making them. There is nothing like being on a night shoot when you’re free and playing and you forget yourself. Then the recording is just a byproduct. But I think, in terms of my going into film and often complaining about the film world, I think there was a lot of projection going on there. I didn’t want to see my own fear of… yeah, my own fear of the great emptiness.

Do you know this poem by Antonio Machado?

I have never yearned for immortality,

nor wanted to leave my poems

behind in the memory of men.

I love the subtle worlds,

delicate, almost without weight,

like soap bubbles.

I enjoy seeing them take the color

of sunlight and scarlet, float

in the blue sky, then

suddenly quiver and break.

The Denis Johnson project, Doppelgänger, Poltergeist, I’m not directing it. I couldn’t get it made as the director even if I wanted to. You can only make so many weird, arty farty films with name actors till the agencies catch on. But also, the last movie I made, The Man in the Woods— I knew while I was making it that it was my final movie as a director. My first movie was a boarding school flick, and so was this last one. I never went to boarding school, but it’s great for writing about teens, because you don’t have to have parent scenes. Like A Separate Peace and Catcher In The Rye— no parents, streamlined. But anyways, regarding Doppelgänger, Poltergeist, it’s about reincarnation. As well as many other things. Twins, New York, September 11th, falling in love with ghosts, how we deal with the suicide of a loved one, being an outsider artist versus being a mainstream artist… It’s just an amazing story that was very familiar to me. And the reincarnation part was one of the components that really clicked. This is the day and age of identity. Where people cling to their identities and things like gender are extremely defining. TV shows and movies and entire careers are built around gender. But in Denis Johnson’s story, identity is more in flux. And reading it almost felt like medicine. It reminded me that clinging to identity is the root of suffering. When I really see someone, they seem to be morphing in and out of old age and youth. And they are a woman one second and a man the next. That, to me, is one of the signs of great acting. When an actor is morphing. There are a lot of Gena Rowlands performances where she looks like a middle-aged lady and then a second later she’s a five-year-old kid. And she hasn’t even moved. She’s just sitting in a booth. Jill Clayburgh is like that too sometimes. Amy Wright, who I think now teaches at HB Studio. Eijirō Tōno. Setsuko Hara. Richard Farnsworth. Garbo. Of course Brando. The bar scene with Eva Marie Saint in On The Waterfront— is he a man or a woman in that scene? Well, in a time of fundamentalism and literalism, he’s a man. But that’s not necessarily the way things are. Or when we watch Dylan in Don’t Look Back at Royal Albert Hall— stuff like age and gender just don’t apply. But that dry way of seeing— where our surface identity is so defining— that’s big business. As long as we are clinging to our surface identity, we’re gonna be somewhat scared and uptight. And scared and uptight makes for loyal, domesticated shoppers. Someone who wrote really eloquently about all this is Rita M. Gross, a great feminist writer. She makes a pretty convincing case that the path to ending patriarchal domination has to lead us beyond gender.

When I was eight-years-old I went to an acting class at HB Studio. It was a weekend thing, mostly improv. I loved it. Then around Christmas time, I got a call. They wanted me to read some Christmas thing with Herbert Berghof himself. Just me and Ol’ Herbert on a stage in front of hundreds of people. I never went back to that class, never acted again. I just wanted to do it for fun, not for a crowd. I think that’s okay. There’s such an emphasis now on being seen. Everything has to be validated by being seen. There is the fear of being forgotten. Or of fading away. But a lot of the time, the more visible something is, the more it is actually fading away. Like, when is the last time anyone truly saw Mona Lisa?

In retrospect, I spent a lot of time trying to get movie stars to be monks. Sometimes quite literally. I wrote a screenplay about Maura O’Halloran, called Mu. Maura was a young Irish woman who went to a temple in Japan and meditated night and day. She had some enlightenment experiences and then right after that, she died. At twenty-seven years old in a bus accident in Thailand. Anyways, for years I would meet or get on the phone with various young movie star actresses and we would talk about Maura O’Halloran. There was so much confusion and fear around the project. I remember one actress saying to me– ‘I don’t understand, how did the old Japanese Zen master know Maura would be able to do the rigorous practice with all those Japanese men?” And I said– “It’s like casting. Like, when a casting director casts you in your first part.” I remember talking to an agent at CAA who was trying to get his client to not play Maura, even though she wanted to. I said– “Listen, she’s gonna go to Japan, learn some Japanese, and shave her head– shaving her head alone will win her acting awards.” I was like a bad car salesman. And the CAA agent replied: “The only project she’s gonna shave her head for is Daughter of Kojak.” Most movies, in essence, are made to reaffirm our delusion of having a permanent, solid self. Hollywood is set up to perpetuate that myth and conditioning. But this was a movie where the main character realizes that she actually has no self. It was a tough sell. Finally, after years of talking to various movie stars about playing Maura, I realized that really I was trying to convince the movie star inside of me to turn into a monk. And by movie star inside of me, I just mean my ego. It was a real relief when I realized that I didn’t actually have to enlist a famous actress to do this work. It wasn’t necessary. But I did have to sit down on a zafu and cross my legs and breathe. That was necessary for me. And remains so.

There are a lot of screenplays sitting on my shelf, like anyone who has been writing scripts for twenty years. One of them is about Philip Guston, called Hoods. It’s about the time where Guston moved from abstract expressionist painting into figurative painting and how the art world ostracized him. The Marlborough Gallery show. I still have Hilton Kramer’s New York Times hatchet job, titled A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum, posted over my desk. Guston was so far ahead of the Times. I think Hilton Kramer probably felt threatened and defensive and maybe even a little jealous. Guston’s new work was so free and wonky and lowbrow. But what is lowbrow? George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strips have more feeling and intelligence than many Pulitzer Prize-winning novels. In the short term, Kramer’s review hurt Guston’s career. But in the long term, it only revealed Kramer to be a fearful protector of the status quo.

There’s a script about rats taking over New York called Rats! Rats! Rats! You know, like huge rats, the size of elephants, roaming through Macy’s. There’s a remake of the Rowdy Herrington movie, Jack’s Back. All kinds of scripts. One of my favorites is something I wrote for Andy Dick and Katt Williams to star in. It’s called Brother From Another Mother. Their father passes away and leaves them a diner in a rough neighborhood in Philly. Andy Dick and Katt Williams have to come together and protect the diner. It’s a completely uninsurable movie, but sometimes you just have to write the thing.

Recently I wrote an in-depth outline/vision statement for a documentary about the baseball great, Eric Davis. Davis is a black man from South Central. I took this project to an African-American filmmaker and producer. I then faded into the background– a white person being the creative source might be problematic for some. Heck, The New York Times recently printed an article saying that any artist who goes outside their own culture is committing an act of minstrelsy. But I feel that it is possible to walk in each other’s shoes. Not just possible, but necessary. If we don’t walk in each other’s shoes, we’re bound to walk in fear.

Sometimes it’s healthy to not be credited. To be a ghost writer. Whatever we want to be or want to have, it is actually not possible because everything is always changing. It’s like grabbing at water. But still we want to be duped. We want to be tricked— ‘oh there’s my name in the credits!’ Or ‘oh— I got published, that must mean something.’ Or, ‘oh I got this award.’ Great, now what? Eventually we give up on getting anything or becoming anything. Nothing can be ours. Not even our own name. Not even our own face.

In terms of the state of independent cinema today, I have no idea. As more and more content is created, it’s hard to know what we are even talking about. One can’t walk down the street without seeing fifty movies being shot on iPhones. If so many people are shooting their movies all the time, and editing their movies all the time, it’s probably a good moment to go back to making stuff with our hands. Or to do theater. The Native Americans were supposedly naive when they thought that cameras disrespected the spiritual world and stole soul. But maybe they were having a vision of our future demise. How cameras would consume us. How eventually we would mutilate our bodies in order to appear a certain way for the camera. In that context, even talking about movies now seems sort of grotesque. We are really killing ourselves with cameras at this point. I understand that in some instances, like with police body cams, cameras are actually saving lives. But for the most part it seems like our obsession with recording everything just leads us further away from reality. For me it’s a good time to ask— what the hell are movies anyway?

Now, if some studio came to me and said ‘we’d like you to direct Doppelgänger, Poltergeist,’ would I be so darn philosophical? Who knows. I think so though. I’m genuinely burnt out on directing. And I’m not very good at dealing with hierarchy. Who’s the director, who’s at the top of the call sheet, who’s got what producer credit…. who gives a shit? You see the same stuff sometimes with religion. People start to buy into the hierarchy. Imagine what Saint Francis of Assisi would say if he was to go meet with Pope Francis in Vatican City. He might say— ‘hey, Pope, let’s go take a walk in the woods, get you out of all this white.’ At the same time, I understand, when someone is going from set to set, year after year, their ranking becomes real to them. Even on a dinky indie set. That’s why I try to have dogs in my movies whenever possible. When there’s a Labrador puppy running around the set and licking everyone, it makes it difficult to take silly stuff seriously.

With The Man in the Woods, I actually opted to not submit it to the critics when I was given that option. The pandemic had just started and I felt that it was in poor taste to put a movie out at all, much less promote it. The compromise was to put it out with no fanfare, no reviews, no trailer, no nothing… Sometimes friends forward me stuff saying how tragically under-seen my movies are, but it’s not tragic to me. If it were, I would have worked with PR agencies more. And generally just been more acquiescent with my agents and managers. I do think that my movies have been misadvertised by distributors, but that too is par for the course. I made these pocket-sized 80 minute comic book poems with the actors that I wanted to make them with and… ya know, if more people saw them, it might have made it easier to get other stuff made, but then again, maybe not. When I look at Francis Ford Coppola, Orson Welles, Val Lewton, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Sam Fuller, Hal Ashby, Nicholas Ray and all the other wonderful filmmakers who have struggled to get their movies made… I mean who am I to complain? If you want to make unique, personal work from the heart, you can’t expect to have the red carpet rolled out for you. The system is really watching to see if you will ingratiate yourself or not.

I haven’t seen many new movies. I don’t really follow Marvel or A24 movies. But one movie I recently saw for the first time was Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes To Washington. When Claude Rains yelled out “Expel me! I’m not fit to be a senator! Expel me! I’m not fit for office! I’m not fit for any place of honor or trust! Expel me!”– it blew me away. It was like hearing a bell of atonement. Instead of virtue signaling or weaseling onto the side of the underdog or twisting the story to make himself look innocent, here was someone who was saying– it’s me! I’m responsible for this whole catastrophe. It’s my greed, and my corruption, and my darkness. In the midst of all the white noise, it rang true.

OUR ORIGINAL QUESTIONS

1. Something that obsesses us about your work, something we’ve been thinking about since we discovered your films in January, 2022, is the internal presence of your anxieties, struggles, mental wars. In an interview, you hinted that the concept of auteur, carried over by the Young Turks of Cahiers du cinéma into the world of motion pictures, could seem surpassed at the present time, reminding us that Sidney Lumet thought that the auteur theory was pretentious. You argued that maybe that “maybe so, but there’s nothing like watching a movie where the director’s vision isn’t tampered with or watered down”. Let this serve as a little justification to the rest of the question. As we look at the different steps you’ve taken in your trajectory, your evolution as a filmmaker, we can see different tonalities: the New York boy reading over and over again Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson, believing that it has nothing to do with Thich Nhat Hanh and his Plum Village. Little by little, the necessity of canalize, reconcile that Manhattan angst with your growing concerns, Zen practices, and how Beat culture gradually was coagulating, loosening its moorings, in your new practices, how natural it became for you over time to relate the experiences of Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac and even Bob Dylan with the bodhisattva. In your films there are these bellicose diatribes, halfway between the promise of a respite that may emerge in a tiny last gesture, and we prefer not to name them dualities. The two forces that pull from Hopper in The Phenom (2016), his father and Dr. Mobley, two different ways of understanding the Darwinist ethic of sports in the USA, also a kind of pedagogy incarnated in the character of Giamatti. We find this too with Ellen in Glass Chin (2014), played by your regular work partner Marin Ireland, trying without insisting too much, without duplicity, to communicate something to Bud, a boxer with not enough time, or rather patience, for truly learning to generate heat in the cold ─and no, it wasn’t just a breathing technique─. Manhattan looming over New Jersey, Los Angeles casting its shadow over John Rosow, the mound that imprisons Hopper.

After this detour, we would simply like to understand, as far as possible, in which way working in cinema, establishing these scenarios, supposes for you too an honest settling of scores, with yourself in the first place, with the world and its overwhelming accelerationism and its immorality then. In the middle of this, your models cannot be missed, maybe victims or combatants of past fights, like those baseball players that spread across the landscape of your films, the remembrance of American football in The Man in the Woods [2020] (we still cannot distinguish the player that appears at the end of the credits in that movie), old and brilliant jazzmen like Fats Navarro, names dropped out, emitting a certain light in the board, like Paul Robeson. We consider you a filmmaker with a moral that can be seen spilled in each shot, consciously or unconsciously, à la Fritz Lang like only an American that has lived in Greenwich Village can be. We get the feeling that you’re on the other side of the joke-wink, accomplice laughter, your seriousness permeates your films without stripping them of their heat. Long story short, and returning to the subject of the author, how do they intertwine all these referents, worldly experience and personal epistemology in the daily practice, so conjunctural, of making movies?

2. We’ve read you in various sites (interviews, articles) being very critical, combative, even angry, about the state of “independent” American cinema. There are several problems that you identify: in the first place, the complexes of some inexperienced filmmakers that must shoot an indie film in order to end up making studio jobs ─like someone who conceives a short film as a springboard for a feature film─, and then, you also perceive a formal stiffness in films called “independent”, certain style to imitate, for example the fetichistic preciousness or coolness of the Criterion Collection, they tend to get on your nerves those products that, due to industrial and distribution reasons, it is in the interest of everyone to label them as indies, when in fact they cover in their conception formulaic processes and, in the worst cases, various test screenings. In short, films that seem packaged by the Sundance Festival itself. With these words, we bring back diagnostics that you made more than ten years ago. So, how do you see today the state of independent American cinema? Could you talk about filmmakers or movies that have caught your attention in recent times as examples of indie cinema, that is to say, as this term was conceived at the end of the fifties, early sixties, an emancipated form attacking from the exterior to fight the studios?

3. During the course of your filmography you have struggled to dignify a type of digital patina that’s so far away from those movies we used to see realized with this kind of technical specs. You began your career by daring to film Bringing Rain (2003) in DV format, with an Ikegami, Sparrows Dance (2012), Glass Chin and The Phenom are films made with a Red Digital, whereas for The Man in the Woods you chose an ARRI. The little project that you devised in 2014 with Liza Weil ─The Situation is Liquid─, with a budget of no more than 3000 $, you chose to shoot it with a Blackmagic Pocket. Although increasingly in vogue in the film industry, this is an equipment we use to find in productions destined for streaming, in film schools, usually handled in inconsistent ways, aberrant, even as a brand image. In your case, we admire the subtle postproduction that you manage to instill in your digital films. What can you say to us about the way you handle these instruments and how these digital procedures affect your films on a budgetary level, but also in terms of shooting and postproduction?

4. You’ve had relations along your career with three different directors of photography. Yaron Orbach took the job in Bringing Rain and Neal Cassady (2007), then in the neuralgic center of your trajectory, we find Ryan Samul, with whom you worked in The Missing Person (2009), Sparrows Dance, Glass Chin and The Phenom, Robbie Renfrow in The Situation Is Liquid, finishing with Nick Matthews in The Man in the Woods. It draws our attention the increase of a higher rigidity, without being in conflict with the breathing of the shots or the sensation of spontaneity that has the spectatorial reception of the dramatic development so concomitant with the display of the découpage. To this respect, it doesn’t cease to amaze us that a film so prepared beforehand in its succession of shots as Glass Chin discovers itself enormously freewheelin’, or that the bunker-shots of Sparrows Dance begin to liberate a sort of expansive energy as the relation between Wes and the Woman in the Apartment progresses, however tied it may be the camera to the tripod; paradoxically, it occurs the opposite in a lot of sanitized films by the Sundance of today ─in which it seems impossible to find revulsives like High Art (Lisa Cholodenko, 1998) or What Happened Was… (Tom Noonan, 1993)─, where that hand-held camera ends imprisoning any glimpse of sincere sentiment. Nevertheless, in The Phenom, we find an aspect already far away from the adaptative capacity of the montage in The Missing Person, serving the shot as a sort of macroscopic lens moving forward with caution, control and security, allowing us to observe the situation with a position that if we call distanced, we’re only doing so in the sense of an inquisitor Philip Marlowe. This control of the shot, its extended duration, and the play with the millimetric zoom in, reaches its top with The Man in the Woods, a film that opens true breaches due to spatial asphyxia, like the irruption of colour, or that intermittent flashback where Paula revises her work on Red Damon.

Could you develop all of this in the manner you’re most comfortable with, trying to provide us with a general vision on how your relationship with your DPs has grown and in which way these persons have contributed to mold with each film a more stable or assured relation with the act of filming?

5. The Missing Person is your film with more transit, scenarios, local movements. In the lodgings, vehicles, in the asphalt and the earth that tramples Rosow following the tracks of Harold Fullmer, his mental wandering finds a natural concomitance. Thanks to his recurrent cab rides, we will be able to identify, in the smile that is drawn on Rosow when he, at last, takes the last ─the negligent driver with the cigarette, the scruffy and caricatured license, etc.─, that the leading man kept deep down inside a somewhat punk conditioning, and to comprehend this, it took us a lot of rides where the previous drivers complained to him about smoking.

When the film was released, you referred to certain stress in the production, lack of time, the inherent difficulties in condensing the energy on the set when the hurry to change spaces lurked; however, all of that, by virtue of knowing how to surround yourself with a team that does not falter, came to fruition, largely due to the tenacity of the inexhaustible Michael Shannon. Since this film, you claim to have learned definitely that the way you most enjoy and feel comfortable with making cinema has to do with embracing a tendency aimed at decreasing the elements to be controlled. Even if we think that The Missing Person is one of your best films, we come to the conclusion that since this movie your cinema has given one step ahead in terms of conceptualization, in the good sense of the word, and that the characters’ mental wars you have been proposing in the whole of your filmography have acquired a concreteness, a level of condensation, very characteristic. You have also affirmed that, at least in your method of working, it’s a mistake to think that your films arise firstly as stories, that you’re a filmmaker, not a storyteller. Can you elaborate on how it connects that increase of conceptualization with your conviction that the films come to life from a certain mood, or atmosphere, even from an image? How does this approach affect the way you have been financing your films?

6. In your films, it is clear the relative isolation of the characters; they tend to constitute a small island remoted from the crowds, the latter, rarely represented ─the uninhabited nights of Glass Chin─, phantomly vacant ─the exterior world in Sparrows Dance─, or conforming a hostile or indifferent block… that opposes the individual ─in The Phenom, the cloud of reporters that pester Hopper, the café clients where he and Dorothy chat, as well as guests of the wagon in The Missing Person─. Sometimes we’re overcome by the sensation that the American people remains completely locked up in their houses getting high with some ersatz, agoraphobic, lost, following on TV any sport or TV spectacle. We perceive too an absence of sonorous racket, contagion or complement of the composition of the frames, an essential silence surrounding the characters, making them confront more directly their own selves, their statements and those of others. Could you tell us about the vision of the world that supports these formal decisions?

7. You don’t need to be a great film buff to be a great filmmaker, however, we’re aware that your vital trajectory is marked by viewings, films, that have imbricated in your existence indelibly. When you were six years old, during your convalescence due to chickenpox, you attended On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) on TV over and over, like a hypnotic dream. Later, your cinephile fever coincided with a great moment of American independent cinema, towards the end of the nineties, where we can find films that dazzled you like The Whole Wide World (Dan Ireland, 1996), Lawn Dogs (John Duigan, 1997) or Whatever (1998), a film by Susan Skoog that got you hooked on the performance without pretendings of Liza Weil. On the other side, you lament that independent directors embarking themselves for the first time in the task of directing end up rerouting their formal projects towards four style elements poorly digested by John Cassavetes, Woody Allen or Jean-Luc Godard, without giving themselves enough space to ponder their references. How do you see in the present day the cinephile health of the new directors? Can you talk to us about filmmakers or films that have been important to you, those that, like a moral strength, have accompanied, formed, instructed you, in the course of your life?

8. Just as On the Waterfront is not a film about boxing, we resist, like you, to think that Glass Chin is, or that The Phenom deals directly with baseball. Nevertheless, we perceive a fundamental bond between these two films, in your concern for a set of leading characters whose spiritual subjugation obeys certain sporting regulations, an institutional severity, with cultural roots, economic tentacles, advertising aspirations, mental and prescriptive cages that prevent, for example, meditating on the wise counsels of their sentimental partners. Sometimes, both Bud and Hopper give the sensation of repeating like a litany, with dubious conviction, a vision of the world, rigged, that clearly will play against them. Like an insistent stone in the way of a country that tries to erase, cover, its brutalities and genocides, we find also in The Man in the Woods that sports record perpetrated by a Native American that resists to be buried in the History of the nation. And while we were talking about the beats, let’s remember the adolescent Kerouac wanting to dedicate himself to sports journalism, redacting privately his leagues of fantasy baseball, or in your film Neal Cassady, when he reproaches Neal for chatting about his «young, damn football talk», and Neal insinuates that maybe Kerouac is only interested in his company in order to get stuff for his writings. What interests you about these personalities ─like Ellen reproaches Bud─ that display a sort of ESPN-conditioned version of the universe? What connections do they have for you these inculcated mental rigidities with the psychic, historic, problematics of North America?

9. Marin Ireland spoke, in relation to Sparrows Dance, about your habit of using actors who had a certain theatrical background and linked this with a fondness for long takes, pretty translucent in that film. However, this does not preclude the use of shots that last a few seconds, nor is a system that you apply to the film´s formal project. This method of yours seems to excite the actors you work with, and not only because of what we’ve read about Marin, but by our own feelings. We tell you without a hint of hyperbole that watching Glass Chin rediscovered us savagely Corey Stoll, his replies, reactions in frontal shots, that talkative personality that domains at the beginning of the film, so that we can later see the tearing of those constraints that make him insecure, condemned to the rearguard, seeing himself locked up between his aspirations and his moral. His spontaneity is a present for our eyes and ears. We encounter again a male performance in American cinema that enchants us. Watching Lawn Dogs, previously mentioned, we could feel something similar in the unbridled aspects of Sam Rockwell and Mischa Barton ─how far from the pose, from the affected, is their dance to the rhythm of, precisely, Dancing in the Dark by Bruce Springsteen, an American sincerity willing to put everything on the line─. In short, it congratulates us that this sentiment seeing Liza Weil in Skoog´s film is ours now too when we watch your movies, with Corey Stoll walking with Kelly Lynch on Christmas Eve while the world is on the verge of collapsing in their faces.

How is your relationship with actors on the set on a daily basis? In spite of their fame, you managed to bring out an infallible truth from Michael Shannon, Paul Sparks, Stoll or numerous performers that we leave behind; many directors with a more laughable pedigree don’t achieve this. By contrast, you seem to have developed a malleable method in which the occasionally long takes, shifting or static, the reaction shots, the possibility of letting an actress look to whom she’s talking to or enunciate herself separated by the frame in her sentimental wanderings, conform a field with endless possibilities. We’d like you to expand about all this, simplifying, the continuous learning about working with actors on a set, but also before arriving there, and the necessary degree of freedom that they should be granted so that they do not only, as you would have said, know how to cry well, or fake accents with extremely gifted precision, but rather to contain an unbreakable truth.

10. We’ve mentioned Springsteen. Now it’s our turn to ask you for something that concerns him ─although we are intrigued and amused by the playful references that you introduce about him in The Missing Person and Glass Chin─. There was a song of his, American Skin (42 Shots), which we know to be of particular significance on your spiritual journey. That song dealt with the brutal murder of Amadou Diallo by four police officers. Reverend Pat Enkyo O’Hara brought up the subject in a Dharma talk, which left you truly surprised. This was the beginning of a process of commensuration, which led you to comprehend that Buddishm was not about resigning or pushing away the culture that you grew up in, nor about not being American. This is in line with the increased assistance to the zendos, the transformation of a disciplined branch of Zen in America that evolves from its apparition as a countercultural force to religious motif that grows and attracts to more and more devouts, inspired by the ever-increasing heterogeneity of the proposal, a process where the hierarchical structures of the past lose importance. The particular chat with the man in the woods that Bud needs when he looks at a shop window with some copies of a book by Pat Enkyo O’Hara, the same chat that they would probably require a large quantity of characters adrift in your films. However, you had it, in a sense, and we would like to comprehend a little how your trajectory evolves in the world of Buddhism, from Nepal to the Dharma programs inside prison centres, passing through the incorporation of American culture, and culminating its inclusion in your writing, both literary and filmic. In what way has Zen practice influenced your manner of facing a film?

11. We end up this interview with your last film until now, The Man in the Woods, a script that, if we’re not mistaken, you had already finished (apart from future revisions and rewrites) in 2015, and which you called then the only script you ever wrote that you thought it could be totally solid. So we’re talking about a project haunting your mind for years. The change of DP, already mentioned, is significant to us and yet your formal project seems a clear evolution from that of The Phenom, with that sequential emphasis in the construction of the scenes, the vital importance of the expansive dialogues between two characters, where a subtle abstraction sparks the films to so many places and moments of American history, like it occurs in, precisely, a short story that we believe it is of particular interest for you to adapt, Doppelgänger, Poltergeist by Denis Johnson. More than a period reconstruction, appealing to nostalgia in a univocal sense, a challenge for the spectator. Cultural references overflow in their specificity, the slang is more complex than ever. However, your discourse is ardently political, a nocturnal roundabout around several open traumas, unbalanced guilts, last-minute healings, dubious masonic lodges, the obsession for a rushing record, and those stained, marginalized, gone mad, by that circle of paranoia. It is inevitable to us to establish a natural relation between the aforementioned short story by Johnson and your last film. Above all, the almost total critic silence about The Man in the Woods, the horrifying lack of information about the film, bother us for real. Can you talk to us about the conception, shooting, editing, and everything that came after, once the film was completed, on a level of reception for this movie? In which way has it been inspirational the work of Denis Johnson in your artistic practice?

We hope that the adaptation of that short story is still in your mind, or at least any other project, and that your spirits don’t come down by the present situation. Like Robert Grainier in Train Dreams was able to witness, maybe the moment when suddenly it all goes black is near, and this time disappears forever.

A big embrace, Noah. Your films have accompanied us and we have developed an honest friendship with them. All the luck in the world.